|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Janine Erasmus

At face value, the activity of electioneering appears to be well-intentioned – a simple act of campaigning for your political party of choice – but dirty tricks and manipulation abound when election campaigning goes into full swing and politicians’ consciences are nowhere to be found.

Politicians often play on voters’ desperation and sensitivities to garner support, turning up at strategic times with food parcels and free t-shirts to distribute to vulnerable people, or invoking veiled threats and stereotypes in their messaging to appeal to gullible constituencies.

This year’s election is no different, except that misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation on virtual platforms are taking on an added presence, and are not always easy to spot. The Daily Maverick recently hosted a training session titled “Spotting False Information During the Elections” that touched on a number of these elements of false electioneering.

“Research internationally … strongly suggests that all of this spikes significantly in advance of elections,” said journalist Rebecca Davis, who moderated. “We are now just more than two weeks out from our own polls on May 29. If you open up social media and take a look at what’s going on there, it is very clear that this phenomenon is playing out in South Africa as much as it has in other large democracies, ahead of these elections.”

To add to the threat, fake news is no longer just a doctored meme here or a misleading headline there – its scale has increased exponentially with the advent of artificial intelligence and deepfake video and audio clips.

False information a danger to democracy

Kavisha Pillay, founding director of the Campaign on Digital Ethics, noted during the session that “during this year of global democracy, the World Economic Forum, the United Nations and various experts in civil society organisations have raised concerns about the risk that false information poses in terms of being able to conduct free and fair elections.”

There are as many as 64 elections scheduled to take place around the world this year. “The more elections that take place throughout the year, the more examples of disinformation emerge and the more complex they become, and the more difficult it becomes to tell the difference between whether or not this is real or fake.”

Despite the amusement value in many of these false information pieces, especially the obviously fake ones, the phenomenon should not be underestimated. Disinformation becoming a real threat to democratic processes all over the world, Pillay added. “The types of disinformation that we’re starting to see have real world impact and can be quite dangerous.”

Manipulating voters

In years to come, will we ever be able to forget the terrifying but hilarious spectacle of former US president Donald Trump seeming to campaign for the recently established Mkhonto we Sizwe (MK) party? A mere glance at the deepfake video – and the X account that shared it – should be enough to raise questions around its veracity, but it is certain that some will be taken in by this electioneering ploy. One hopes they will also be convinced by the equally hilarious deepfake videos countering Trump’s MK statements and urging voters to rather support the IFP and EFF, respectively.

On another note, we are familiar with the same old rhetoric spouted by the ANC every election, that various social services will disappear should it lose power. This callously plays on the fears of the poorer sections of the population who rely on these services, which will not go away no matter who is in power. In fact, several contesting parties have promised to increase the social benefits if elected into power, using the ANC’s own disinformation tactic against it.

One of the ruling party’s most experienced politicians and former president, Jacob Zuma, now leading the MK, claimed during his campaigning efforts that he had ended load-shedding, another hot topic of this year’s elections.

These are all elaborate, far-reaching claims, but disinformation can be as simple as omitting a few numbers in a statistical analysis or sharing a photo under a deliberately false context. It is up to the consumer of news to be vigilant and open-minded, prepared to ask questions, and do their own research.

Disingenuous and misleading

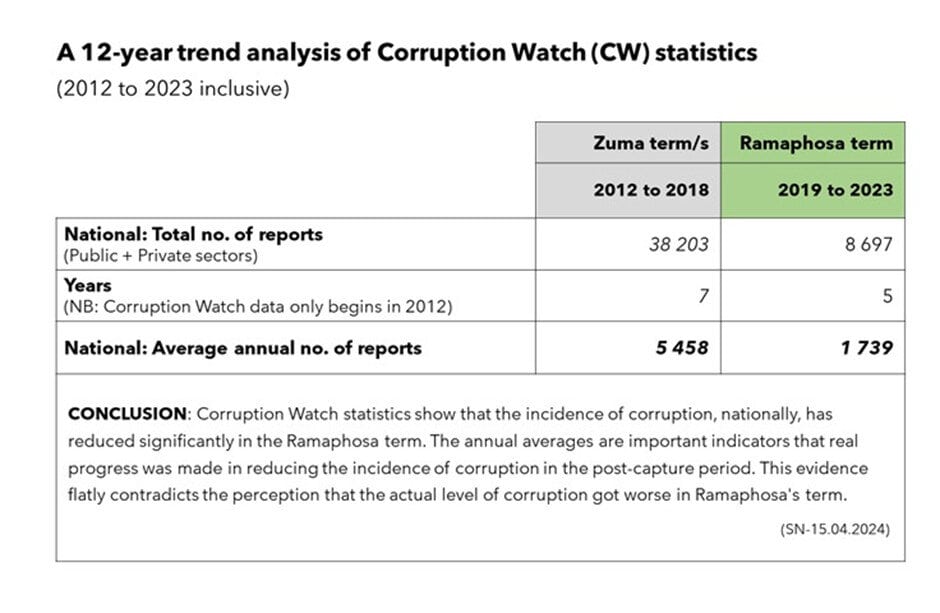

Organisations such as Corruption Watch (CW), which have public profiles, can also be used to push narratives that don’t have credibility. One recent example of disinformation stems from content in our 2023 annual report, released at the beginning of April this year. It is a simple table, not involving deepfakes of any kind, but containing disinformation nonetheless because it uses inaccurate figures and arrives at a false conclusion, under the guise of being informed by CW’s research.

From the X account of one Kgoši Maepa, a graphic was shared last month that incorrectly claims its content to be from CW.

The accompanying text ran as follows:

“BREAKING NEWS: Corruption Watch [CP] report shows a reduction of corruption in South Africa! Corruption under President @CyrilRamaphosa has reduced significantly since 2019 to 2023. More work needs to be done. Science and numbers don’t lie! #VoteANC2024 #LetsDoMoreTogether”

The two hashtags that Maepa added at the end clearly signify that this is an election-related post and that he was campaigning for the ANC, having hashtagged that party’s official slogan for the 2024 elections.

We can therefore deconstruct this information as a product of electioneering which tries to convince people that corruption has decreased under the Cyril Ramaphosa regime by providing ‘evidence’ in the form of a badly analysed statistic.

The first thing that leaps out is that these figures are indeed related to CW research, but they are not accurate, nor is the analysis and conclusion our work. As CW, with a handle on the many different factors which affect the whistle-blowing culture in South Africa, we would never come to such a simplistic, flawed conclusion.

Let’s look at it in depth.

The analysis has several gaps, the first of which is that the figures only reflect corruption reports brought to CW. They don’t reflect the numerous other sources of corruption complaints, such as the various government anti-corruption hotlines, and other social justice or dedicated whistle-blower organisations, among others.

CW cannot possibly be the only source if the author wants to present a comprehensive analysis which even remotely approaches accuracy, of the national corruption problem.

Therefore this simply cannot be presented as a believable state of corruption in South Africa and it certainly cannot be construed as a validation of Ramaphosa’s valiant efforts to reduce corruption – because other sources tell us that the country is going downhill on that score.

A quick look through all of CW’s annual reports since 2012 and a record of the corruption report numbers presented there shows clearly that the numbers in the graphic are inaccurate. The table below shows a very different picture:

| YEAR | NUMBER OF REPORTS | |

| 2012 | 3223 | 2012-2018 Total number = 24 502 Average = 3 500 |

| 2013 | 2262 | |

| 2014 | 2714 | |

| 2015 | 2382 | |

| 2016 | 4391 | |

| 2017 | 5334 | |

| 2018 | 4196 | |

| 2019 | 3694 | 2019-2023 Total number = 16 000 Average = 3 200 |

| 2020 | 4780 | |

| 2021 | 3248 | |

| 2022 | 2168 | |

| 2023 | 2110 |

It is not clear where the figure of 38 203 for 2012-2018 in Maepa’s table comes from, but it doesn’t come from CW. Also, the figure of 8 697 for 2019-2023 represents only half of the number of reports received by the organisation during that period. There seems to be a deliberate effort here to mislead followers.

What also jumps out from this very superficial analysis is that the average number of corruption reports may have decreased, but only slightly. Certainly not enough to make a difference in the life of the ordinary South African.

Other factors in force

There are other factors which CW is aware of, which may have influenced the numbers of reports at certain times. In 2016, for example, we embarked on advocacy work calling for transparency and public participation in the appointment of the next public protector. To accompany this campaign, we did extensive marketing and public awareness work which boosted our profile and resulted in the jump in the number of reports we see from 2015 to 2016. One cannot simply conclude that corruption increased because the number of reports increased.

This was the forerunner of our greater leadership appointments campaign, where we advocate for appointments to important government institutions, especially those in the law enforcement and criminal justice systems, to be done fairly, transparently, and on merit – rather than being politically motivated as they have been for years, because we know how that worked out.

We also remember that with the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, huge corruption was exposed and is still being investigated. During that year we received a flood of reports related to the pandemic, which can be seen in the jump between 2019 and 2020, and the dip between 2020 and 2021.

In the last two years, where we see the lowest numbers of reports yet recorded, there have been internal dynamics and adjustment of structures at play, which have influenced those results. It certainly cannot be assumed that corruption has decreased merely because CW received fewer reports.

So the moral of the story is: voters who are invested in making informed decisions about who to vote for, should not believe everything they read, especially on social media. They must interrogate the information with an inquiring and critical mind and be prepared to research the topic by looking for alternate, credible sources of the same information, checking the author and the date, turning to fact-checking resources such as Snopes, Full Fact, and Africa Check, and other measures.

In today’s world, there is no excuse for believing disinformation when the resources for debunking it are out there.