|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

| SAAC HOME AND LATEST NEWS | ABOUT THE SAAC PROJECT | SAAC INFORMATION AND RESOURCES |

WELCOME TO THE Strengthening Action Against Corruption (SAAC) Project MINI-SITE!

This is the home page of our SAAC mini-site, and here you’ll find a short introduction to the project, as well as the latest news and developments, from report launches and other valuable information to activities and events. To see other pages in this mini-site, use the navigation aid just below the main image on this page, or simply click on About SAAC or SAAC information and resources for more information.

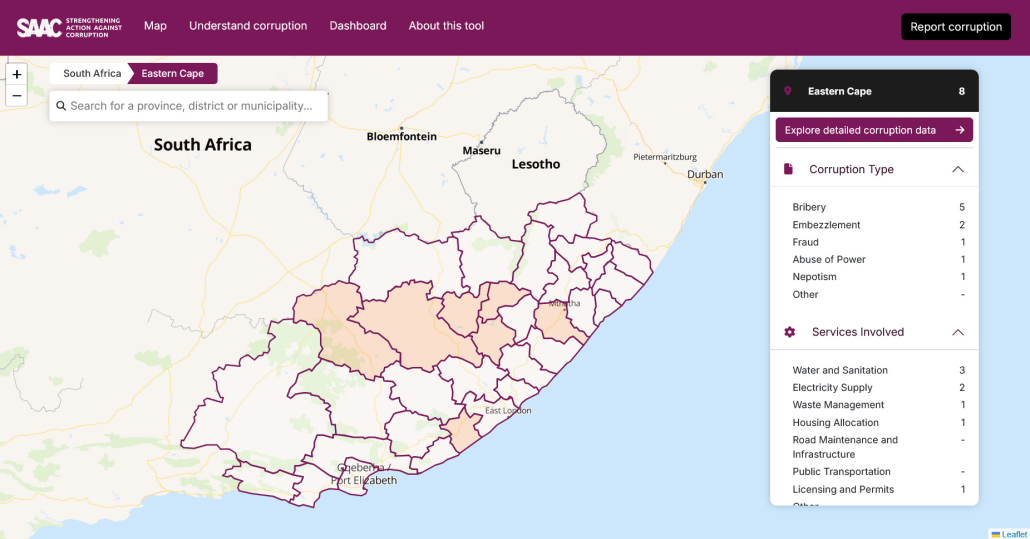

Just launched – our corruption reporting tool for the Eastern Cape!

The Local Government Anti-Corruption Digital Technology Tool (DTT) is a citizen-focused platform designed to promote transparency, accountability, and active civic participation in local government. Developed under the Strengthening Against Corruption (SAAC) project, the tool empowers residents to identify, understand, and anonymously report corruption-related issues affecting their communities.

Responding to the real challenges of municipal governance, the DTT provides easy access to information on public services, municipal budgets, service delivery performance, and the roles and responsibilities of local officials. Its user-friendly interface guides citizens in recognising red flags of corruption and offers secure, anonymous channels for reporting misconduct – helping to protect whistle-blowers and promote accountability.

In addition, the DTT serves as a hub for civic education, offering practical resources to support community-based organisations (CBOs) and individuals in engaging meaningfully in local governance processes.

Click on the map to go to the tool.

The latest SAAC news

SAAC stories from the ground

Corruption is undoubtedly a serious problem in South Africa and all provinces, with no exceptions, face its repercussions in the form of poor service delivery and improper management of resources. Residents of the Eastern Cape, however, have seen a new wave of activism brought about by the SAAC project.

Below we publish some of the anti-corruption community action undertaken as part of SAAC. We will add to these on an ongoing basis, so visit this page regularly. Click on the headings below to expand the stories, and click again to condense them:

The beauty of Alicedale eclipsed by hardships for locals

It is often lauded as one of the most picturesque areas of South Africa, with green hills that span over hundreds of kilometres. Nestled in the Makana Local Municipality, the region of the Eastern Cape province, Alicedale is a small town that boasts some of the country’s most loved game reserves. Among these is the world-famous Addo National Elephant Park.

Municipalities.co.za describes it in this way: “The Makana area has nearly a million hectares devoted to game. A range of public and private nature reserves span the area, from the world-famous Shamwari in the west to the magnificent Double Drift and Kwandwe Reserves in the east.”

Anyone reading about Alicedale would imagine these tourist attractions bring good economic opportunities that boost the tourism sector for this semi-rural community and surrounding areas, but this is not necessarily the case. Many of Alicedale’s residents are aggrieved over what they describe as neglect and disregard from their municipality. The tourist attractions – renowned as they are – come at a cost for them of irregular supply of clean water, an issue that has plagued the area for a long time, with little or no acknowledgement from the municipality.

Community leader and CARE Alicedale director Phumla Gojela calls it an injustice and infringement of the constitutional rights of residents. They have to struggle to access water and when it does reach their taps, it is often not of the best quality for drinking.

“Alicedale’s water supply system was compromised after the municipality allowed the privately owned game reserves to draw water from the local dam and river for the benefit of the wild animals,” says Gojela.

“The situation worsened when an old farm owner started his own privately owned game reserve. The farmer built a brick wall around the dam nearest to him, blocking the natural flow of water to our river. This has further reduced our access to water. This was clearly visible during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021.”

Half-hearted municipal effort

The urgency for CARE Alicedale was in addressing the matter with Makana. Gojela told the Strengthening Action Against Corruption (SAAC) team that numerous complaints were made to the municipality, with CARE providing evidence in the form of pictures, of residents resorting to walking far to fetch water from the river.

Makana’s response was to provide water tankers, a solution that ensured the provision of clean water, but was not sustainable in the long term.

SAAC was launched in 2024 with a team from Corruption Watch, the Social Change Assistance Trust, and Transparency International charged with identifying CBOs across the Eastern Cape to lead mobilisation efforts for administrative accountability from local government, from the ground. The CBOs are encouraged and have been trained through various workshops held in 2024 and 2025 to raise awareness about service delivery challenges in their communities as well as how to hold public institutions at local government level accountable to the service delivery principles of the Constitution.

No community consultation

Gojela says for the most part, the grievances that Alicedale residents have with their municipality stem from years of poor service delivery and planning for all residents, not just the tourism-focused businesses. The community does not get consulted in terms of spatial planning by the municipality as well as the allocation of services such as water. Over time, this has resulted in community members having to regularly fetch water from springs and other natural sources in the area that are also used by game.

This has created challenges for small businesses in the area and for many in the community who have to factor in the task of fetching of water into their daily schedules. Some of these are schoolchildren who end up missing out on crucial learning time. Although Gojela acknowledges that developing the area’s tourism sites over the years was good, it should not have been at the expense of the communities that are now neglected and without clean drinking water. She is of the view that they were also not prioritised in the planning process for the area.

Taking on the war on poor water supply from the ground

The community of Qongqotha village in Qonce in the Eastern Cape has taken on the Amatola Water Board (AWB), demanding that it addresses issues of poor and irregular water supply and damages to homes caused by what they say is a poorly planned construction of a reservoir in their area.

The ability to own land in South Africa is a privilege that not many can claim. So, when one lives in a poor, rural area with little or no development, it becomes a source of pride for their family. For many such families across the rural areas of the Eastern Cape, the harsh realities of unemployment and poor or no development bite harder when they have to fight to keep their homes safe from harmful infrastructure development projects. Some of them live in Qongqotha village in Qonce, formerly King Williams Town, in East London. It is one of numerous villages that fall under the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality. Qongqotha is home to about 1 300 residents and is made up of just over 300 families.

As with many other areas of the Eastern Cape, development in the supply and management of water infrastructure has been slow, with the area relying on a bulk water service system administered nationally by the Department of Sanitation. Several years into the advent of the reconfiguration of the province’s regions after 1994, the Amatola Water Board (AWB) was established as one of nine across the country that oversee water infrastructure development and supply management in the provinces.

Qongqotha’s turn to get its own improved reservoir initially began in 2009 in an effort to improve water supply services in the area. But some time into the project, challenges arose about the choice of location for the construction of the infrastructure. Some residents’ homes stood in the planned path of the pipelines to be installed, but the work had already started when this was discovered. Some residents were receptive to relocation offers, while others were not prepared to relinquish their homes. To avoid damages to the homes that had not been demolished, some of the pipelines were rerouted, but for some families this action came too late, with damages to their houses already visible.

Demanding accountability

Nomiki Mathosa is a community activist and coordinator with Entlango Primary Agricultural Cooperative. For the most part her role has involved advocating for accountability from institutions offering services to the people of Qongqotha and surrounding areas.

She cites one elderly resident of Qongqotha, whose name is known to Corruption Watch (CW), as one of the people who have brought complaints to Entlango seeking help. According to Mathosa, the resident recounted how as far back as 2014 his complaints to damage to his home, which he noticed prior to the recent renovations, did not yield results. The ground around his home always becomes waterlogged due to leakages from the pipes that run underground. More damage came, however, with the recent construction: some of the walls of his house had started to crack from the pressure caused by the drilling nearby. Entlango committed to following up with AWB on his behalf, but their efforts too would go unresolved.

The team resolved early in 2025 to conduct an audit of all affected households to make for a stronger case with AWB. A site visit to the construction area was arranged for 22 August 2025, with an AWB management team meeting Entlango representatives, followed by another communication lull until a follow-up letter was sent, requesting commitment to the points discussed during the site visit.

It was only after the letter, in which several stakeholders such as the provincial public protector’s office and CW were copied, that Mathosa received a response to a request for a community meeting meant to provide residents with a platform to speak out about their challenges.

Mathosa explains: “There was no proper consultation where the people can say it was a response maybe to water shortage or wanting to expand areas of separation for the department of water affairs or Amatola… what came to the village is that a new reservoir is going to be built, but for people to have a proper understanding of why it was being extended, there was no consultation.”

She adds that the development was done haphazardly, with only the elder members of the community being able to recall that there had been talks of building a reservoir in the distant past. Some residents feel aggrieved that the urgency of the impact of the poor construction is not recognised by either the AWB or the municipality. “All the houses within a certain radius from the construction site have mould,” Mathosa explains.

Part of an organised movement

Entlango is one of about 20 community-based organisations across the Eastern Cape that were earmarked to be part of the Strengthening Action Against Corruption (SAAC) project in 2024. The programme specifically targets community advice offices/civil society organisations (CSOs), equipping them with the knowledge and resources needed to identify and address corruption and gaps in accountability in relation to service delivery. By supporting these organisations in mobilising their communities, SAAC fosters a culture of accountability and transparency that is fundamental to anti-corruption efforts in South Africa.

The SAAC partners include CW, the Social Change Assistance Trust, and Transparency International, with each organisation playing a different role. For cooperatives like Entlango, the support both financial and otherwise has meant that mobilising communities that are affected by poor service delivery is more organised and structured.

On 11 November, the officials at Entlango facilitated a meeting at which an AWB delegation, along with the ward councillor for their area, were invited to address the community and hear of their struggles with getting regular water supply. From the pipe leakages to the dry taps in their community, they made their case, and were promised that their grievances would be addressed.

Emboldened by the community’s eagerness, Entlango’s next step is to submit an advocacy report to the provincial government, with the help of CW. The report notes: “At this meeting, the management team listened to the issues and informed the delegation that the grievances would be referred to AWB’s head office in East London.”

Toolkit for assessing corruption risks in local municipalities of South Africa – December 2025

Download our new Toolkit for assessing corruption risks in local municipalities of South Africa.

The SAAC team has developed a bespoke corruption risk assessment toolkit to generate evidence on corruption risks within local municipalities in South Africa and use the evidence to advocate for reforms. This will strengthen the capacity of community-based organisations (CBOs) and community advice offices (CAOs) in the Eastern Cape to develop and advocate for context-specific responses to corruption. Their proximity to local communities enables these organisations to uncover corruption and its risks that may otherwise go unnoticed, and advocate for targeted interventions that resonate with local realities.

Anti-corruption Guide on Understanding Corruption and Public Accountability – July 2025

Download our Anti-corruption Guide on Understanding Corruption and Public Accountability.

The document explains corruption in understandable terms, and offers advice on topics such as how to hold municipalities accountable, identifying what is corruption and what is not corruption, how to recognise various forms of corruption, how to be an active citizen, and more. It also provides a useful infographic of the structure of government.

Report-back from the second Corruption Busting Bootcamp – May 2025

We conducted our second Corruption Busting Bootcamp (CBB2), which took place from 19 to 23 May 2025. While the first bootcamp had the purpose of introducing the CBOs and CAOs to the project and its objectives and to train them on how to achieve its goals, CBB2 touched base on the progress of their campaigns in the community. There was a clear and palpable distinction between the two events in terms of how CBO and CAO leaders received information as well as how they expressed their roles in communities.

We plainly saw how the elevated confidence shown at CBB2 meant that our activists have now transitioned into leadership roles with clear strategies for how to mobilise their communities into forming organised structures that demand accountability safely and effectively.

For more information about the happenings and discussions that took place at May’s bootcamp, please download the CBB2 report, or read it online below.

Youth Ambassador for Accountability (YAfA) workshop 1 – April 2025

At the beginning of April 2025 we hosted a week-long training workshop for a cohort of young people, nominated through their community work across different parts of the Eastern Cape. They received training in advocacy work, communications, and media, and how to hold each other accountable as part of the SAAC’s Youth Ambassador for Accountability (YAfA) programme. The workshop was successful in bringing to the fore the key issues that young people affected by corruption and poor governance see in their communities every day, and encouraging them to be able to confidently answer the question: ‘what can I do about it?’ Read more in this short opinion piece.