|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Zaheer Cassim

By Zaheer Cassim

Additional reporting by Nicky Rehbock

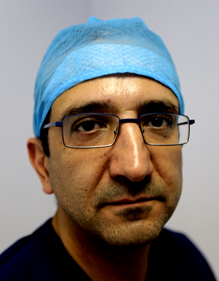

Paediatric surgeon Dr Bob Banieghbal takes a sip of his coffee at the cafeteria in the lobby of the private Park Lane Hospital. Sitting with both hands behind his head, he stretches back and begins to talk about his career in medicine that began nearly two decades ago. He has spent the bulk of it, 14 years, working in the public sector in Gauteng.

His first stint, of nine years, was at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto and after that he worked at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital. He says the widespread abuse he witnessed during this period, of doctors doing private practice work on the state’s time, as well as a lack of opportunities to grow, drove him away from the public service.

During his time in public healthcare, Banieghbal says he saw many senior specialists, who were earning hefty salaries, skip work to run their own practices. This not only cheated state patients out of medical care, it also affected the transfer of knowledge from senior practitioners to junior doctors who needed their mentors to on site during procedures.

"Ideally medical practice is based on a pupil-mentor setup. The more senior person teaches the more junior person and gradually the junior person becomes more experienced. If there is no contact [due to the senior not being at the hospital], how can the junior person ever become senior?" he asks.

While working at Charlotte Maxeke Hospital in 2006, Banieghbal recalls one operation during which a junior surgeon desperately needed the advice of a specialist, who was nowhere to be found.

"A junior guy was working on an appendix and found a mass [tumour]. That person didn't know what to do. He called his seniors, but they wouldn't answer because they were in private practice operating, so the junior just closed the patient up," he explains.

State doctors are allowed to undertake paid work outside the public service, according to the Public Service Act’s policy of Remuneration Work Outside of Public Service (RWOPS), but the rules are made clear: private jobs must not interfere with public-sector commitments.

At first, RWOPS incentivised doctors to keep working in state institutions because the pay was generally lower than in private practice. However, Banieghbal says this was heavily abused: he’s seen many state specialists in Gauteng who used RWOPS as an excuse to run fully fledged private practices.

Better pay to solve the problem?

In 2009 Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi spent R1-billion on dramatically revising the pay structure for public sector doctors.

Banieghbal said this saw his salary increase quite substantially. More experienced specialists received an even larger pay rise. This, coupled with a 13th cheque, medical aid, pension, 25 days of leave per year, commuted overtime and in some cases a rural allowance, made being a state doctor a cushy job.

The saga of doctors doing private work on the state’s time came to a head earlier this year in Gauteng when the province’s health department became stricter about enforcing RWOPS policy, following a report by the Public Service Commission (PSC) which found that 50% of specialist doctors run private clinics or practices.

Mass exodus

The tougher stance saw an exodus of 21 specialists at Charlotte Maxeke Hospital: “Some of them are leaving because of personal reasons, while others have decided to join private practice on a full-time basis following strict control measures put in place by the department in relation to Remuneration Work Outside of Public Service,” the Gauteng health department said in statement released late in May.

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi has also made it a priority to stop the state doctors who are cheating the system. Last month, he was quoted in City Press as saying he would seek the help of the South African Revenue Service to catch public doctors who are not declaring tax on their private work.

A Gauteng anaesthetist who didn’t want to be named told Corruption Watch that one of the reasons doctors don’t declare tax made from their private-sector work is because this can be used as evidence of evading their public sector duties.

Motsoaledi’s department is already investigating more than 500 doctors in Limpopo, Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal for defrauding the public sector through unpaid taxes.

Not just Gauteng

Corruption Watch was alerted to this abuse of public resources in KwaZulu-Natal when we were tipped off by a department head at a hospital on the South Coast:

"There are no checks and balances here. They [specialists] come in the morning or they don't come at all," according to the source. "The government has done a lot; they have put in the money. Some of the specialists here earn better than doctors in the UK."

"It's just greed," he added.

Banieghbal says he often looks back on his career as an employee of the state, and thinks about all those patients who didn’t get adequate care because senior doctors were too busy worrying about their own wallets.

"At the end of the day, the fatalities will increase if this behaviour doesn’t change," he explains.

Last month Charlotte Maxeke Hospital began a process of recruiting specialists to fill posts left vacant by the 21 resignations.

“Since last week Thursday, 23 May, the hospital has been interviewing medical officers, registrars and anaesthesiologists to replace those who have resigned,” said Health MEC Hope Mankwana Papo.