|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“We will take back those houses if you sell them for profit, because we build them for a purpose. Put it away safely.”

“We will take back those houses if you sell them for profit, because we build them for a purpose. Put it away safely.”

This was reportedly said earlier this year to a group of residents of the Sol Plaatjie municipality, who had gathered to witness the handing over of title deeds to beneficiaries of over 1 000 RDP houses. It is these title deeds that were meant to be put in a safe place. Mayor David Molusi urged the residents to keep the documents safe “as it is also your good story to tell. It is your child’s legacy.”

One of the residents, interviewed by local newspaper Express Northern Cape, expressed her happiness and disbelief at finally getting her house: “I have been living in [Phutanang] for more than eight years and have always been asking myself whether the house is really mine. I was afraid that one day someone would come and chase me out of it.”

Her fear is not unfounded, and she shares it with many housing beneficiaries who remain uninformed about the processes of housing subsidy benefits in South Africa. One of the key provisions of the RDP housing system is that a beneficiary may stay in the house for up to five years before they can receive a title deed for it. In that five-year period, they are not allowed to sell the house, and should they need to move elsewhere as is often the case with family or work obligations, the onus is on them to inform the authorities of their departure. This will be helpful if they intend to seek another housing opportunity again after relocation.

Molusi was spot on about the houses being a legacy for children, because with the title deeds in hand they can choose to sell or rent out their homes for financial benefits in future. The mayor perhaps erred, however, in making the threat of taking away title deeds from people like the resident who had insecurities about a house she had lived in for eight years. He might also have missed the opportunity to inform and reassure his constituency on the rights and responsibilities that come with securing title deeds for their homes.

Waiting for their place in the sun

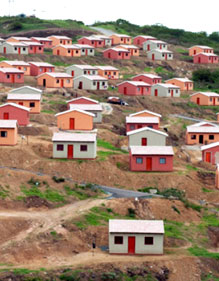

Millions around the country apply for housing opportunities when prompted to do so, going through the process of being vetted according to strict criteria, before eventually receiving the good news that they can now take possession of the keys to their new home.

However, there are possibly hundreds of thousands of people across the country who are not living in the housing units allocated in their names – yet this story is not commonly told. This group includes those would have relocated between applying and formal allocation, who are recognised by the system as having benefitted, but remain desperate for a home.

One such “beneficiary”, John Twala*, on whom Corruption Watch reported recently, is a frustrated man. Twala applied for an RDP house 18 years ago, but was forced to move from his residence two years later to attend to a family emergency. He received a housing subsidy in the space of the two years, but because he had failed to follow up on his application – and the municipality might have sought him for some time without success – he is now without the house that he needs.

“It came as a surprise to me when I went to re-apply [for another housing subsidy years later]. I mean, I have had a house all along, but did not know it. According to the system, I was told that I did not qualify for a second application,” the father of two told Corruption Watch.

The organisation is now working with Twala to determine the process of deregistration from the system, with the intention of re-applying once this has been done.

A simple process to sort out

Motsamai Motlhaolwa, of the Gauteng department of human settlements, explained to Corruption Watch that the deregistration process is a simple one, provided Twala has not yet claimed payment from the department.

“If payment hasn’t been claimed, then the applicant can visit their nearest housing subsidy unit [in Twala’s case, Krugersdorp in Mogale City],” he said. “He will be given a cancellation form which he will get stamped by a commissioner of oaths at the nearest police station, and certify his ID copies, and then submit it to the subsidy unit.”

Once an application for a housing subsidy has been approved, the applicant is issued a slip that shows that their details have been uploaded onto the housing database. Also on the piece of paper is the stand number they have been allocated.

Motlhaolwa confirmed that Twala’s subsidy application was indeed approved and that no payments have been claimed on it. Twala’s real name is known to the department.

“He must visit the West Rand Regional Housing in Krugersdorp with a certified copy of his ID and an affidavit stating that he requests to be cancelled on the housing subsidy system as he didn’t benefit from the project.”

There have been several cases of deregistration of RDP beneficiaries in past years. Although we asked Motlhaolwa about the estimated annual figures for Gauteng, he did not provide these.

There are rules for beneficiaries of the RDP housing programme and subsidy holders stand to lose out on their homes if they do not abide by them.

By law, an applicant of an RDP house must:

- be a South African citizen;

- be over 21 years of age;

- have a total household income of less than R3 500 per month;

- be married or live with a partner or be single and have dependants (children you are responsible for);

- never have owned a house or a property anywhere in South Africa.

* Not his real name