|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In this election season, it is important to consider the laws that affect our day-to-day life, and beyond. Why? Because the political parties we support send their elected representatives to Parliament to work on our behalf in making laws, among other important functions.

Therefore, we must carefully consider who to give our vote to – is it a party with a track record of making promises that it does not keep? Is it a new party formed by people of good reputation, whose manifesto focuses on the issues that are important to us? Is it an opportunistic party that jumps onto every bandwagon but has not produced any work of substance?

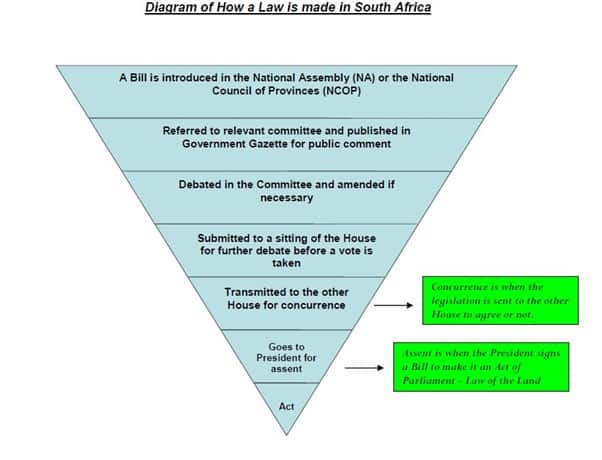

While we ponder our choice, it is useful to demystify the process of making a law and recognising that it is a lengthy process (sometimes far too lengthy). Understanding Parliament’s functions is part of being an active citizen, one that will not be afraid to make their mark on the ballot paper when the time comes.

Source: Parliament of South Africa

What is a law?

Law is a system of rules, usually enforced through a set of institutions to regulate human conduct. It shapes politics, economics, and society in many ways. There are different types of laws such as contract law, property law, trust law, criminal law, constitutional law, and administrative law. Constitutional law provides a framework for the creation of law, the protection of human rights, and the election of political representatives. Law also raises important issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice.

How a law is made

Parliament is the national legislature (law-making body) of South Africa. As such, one of its major functions is to pass new laws, to amend existing laws, and to repeal or abolish (cancel) old laws. This function is guided by the Constitution of South Africa, which governs and applies to all law and conduct within South Africa.

Parliament has legislative authority (the right to make laws) in the national sphere of government. Provincial legislatures exercise the same powers in the provincial sphere of government, and municipal councils in the local sphere of government.

The process of making a law may start with a discussion document called a Green Paper that is drafted in the ministry or department dealing with a particular issue. This discussion document gives an idea of the general thinking that informs a particular policy. It is then published for comment, suggestions, or ideas. This leads to the development of a more refined discussion document, a White Paper, which is a broad statement of government policy. It is drafted by the relevant department or task team and the relevant parliamentary committees may propose amendments or other proposals. After this, it is sent back to the ministry for further discussion, input, and final decisions.

Who makes the laws?

Both Houses of Parliament, the National Assembly (NA) and the National Council of Provinces (NCOP), play a role in the process of making laws. A bill or draft law can only be introduced in Parliament by a minister, a deputy minister, a parliamentary committee, or an individual member of Parliament (MP). Most bills are drawn up by a government department under direction of the relevant minister or deputy minister. This kind of bill must be approved by the Cabinet before being submitted to Parliament. Bills introduced by individual MPs are called Private Members’ Legislative Proposals.

Types of bills

The Constitution describes four types of bills. Each type has a different passage to becoming a law and usually fits into only one category. If a bill does not clearly fit onto one category, it is usually redrafted or split into more than one bill.

Section 74 bills deal with constitutional amendments (bills amending the Constitution):

- Amending the Bill of Rights requires a vote of two-thirds of the NA and the support of six provinces in the NCOP. Amendments must be passed by the NCOP. All amendments affecting the provinces must be passed by both Houses.

Section 75 bills are ordinary bills not affecting provinces:

- These bills can only be introduced in the NA and once passed, are sent to the NCOP for concurrence. A bill is passed when there is a majority vote by delegates present, in favour of the bill.

Section 76 bills are ordinary bills that affect provinces:

- The bills are introduced in either the NA or NCOP and must be considered by both Houses. In the NCOP, votes are by provincial delegations and at least five provinces should vote in favour of a bill before it is agreed to. Bills are usually considered by a provincial committee, which may hold public hearings on the bill for comments and suggestions.

Section 77 bills are money bills such as appropriations, taxes, levies, or duties

- Money bills allocate public money for a particular purpose or imposes taxes, levies, and duties. They can only be introduced by the minister of finance in the NA. In terms of the Money Bills Amendment Procedure and Related Matters Act, 2009 (Act No 9 of 2009), Parliament may amend money bills.

What is tagging?

As soon as a bill is introduced in Parliament it needs to be classified into one of the four categories mentioned above, by the Joint Tagging Mechanism (JTM). This is called tagging and will determine the procedures the bill must follow to become law. The JTM consists of the speaker and deputy speaker of the NA, and the chairperson and permanent deputy chairperson of the NCOP. These office-bearers are assisted by parliamentary legal advisors.

From bill to law

- The State Law Advisors certify a bill as being consistent with the Constitution and properly drafted.

- Before a bill can become a law, it must be considered by both the NA and the NCOP. It is published in the Government Gazette for public comment, unless it is very urgent, and then referred to the relevant committee. It is debated in that committee and amended if necessary.

- If there is great public interest in a bill, the committee may organise public hearings.

- Once it has decided on its version of the bill, the committee submits it to a sitting of the house for further debate and a vote. A bill could be referred back to a committee for more work before a vote is taken. The bill is then referred to the other house for its consideration.

- If the bill passes through both the NA and the NCOP, it goes to the president for assent and signing into law. Once it is signed by the president, it becomes an Act of Parliament and a law of the land.

National vs provincial

When is a lawmaking matter national and when is it provincial?

- Schedule 4 of the Constitution lists the functional areas in which Parliament and the provincial legislatures jointly have the right to make laws. This includes things like agriculture, health, housing, the environment, and education (but not tertiary or higher education).

- Schedule 5 of the Constitution lists the functional areas in which only the provincial legislatures may make laws. This includes things like provincial roads and traffic, liquor licensing, provincial planning, and provincial sport.

In exceptional circumstances Parliament may make laws that fall under Schedule 5 to maintain national security, maintain economic unity, establish minimum standards for service delivery, or to prevent unreasonable action by a province which affects the interests of another province or the country.

Did you know?

The apartheid legislation in South Africa was a chain of different laws and acts which helped the apartheid government to enforce the separation of different races and consequently cement power. With the enactment of apartheid laws in 1948, racial discrimination was legalised. One such example of discriminatory legislation was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, Act No 55 of 1949, an apartheid law which banned marriages between people of different races. This law was enforced for 36 years and was only repealed in 1985.