|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By David Lewis and Michael F. Breen

First posted on Foreign Policy

US president Joe Biden launched a new initiative last month to focus the government on the fight against corruption, a struggle he called “essential to the preservation of our democracy and our future.” The stakes are indeed high, and Biden was right to commit to working with partners abroad, because stopping graft in one country often depends on other nations lending a hand.

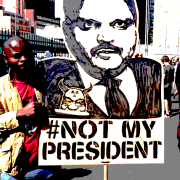

Nowhere is this dynamic clearer than in South Africa, where a broad effort to end a sordid chapter of official corruption has led to former president Jacob Zuma being jailed for refusing to testify on the matter. A key piece of the country’s reckoning depends, though, on whether its partners from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to the US will act to help bring justice in another high-profile corruption case – one that highlights the importance and elusiveness of international cooperation.

The same day Biden announced his anti-corruption initiative, South African law enforcement officials brought long-anticipated charges for fraud and money laundering against members of the notorious Gupta family. Allegations against the Guptas by investigative journalists and whistle-blowers helped prompt the 2018 creation of South Africa’s commission of inquiry into ‘state capture‘, the decade-long period of grand corruption in which the country’s top leaders ceded control over state resources to private business interests and subverted institutions charged with keeping the government accountable.

That commission is now preparing its findings and recommendations – without the testimony that Zuma and the Guptas have refused to provide. Nevertheless, its success in shedding further light on abuses of the public trust represents a major achievement.

South African authorities have sought Interpol notices and sent extradition requests for two of the Gupta brothers, their wives, and some business associates.

Ending this kind of corruption, however, will require South Africa to go beyond establishing a historical record; it must hold individuals to account, including through criminal prosecution. But Ajay, Atul, and Rajesh Gupta – three brothers and businessmen with a global web of financial ties who allegedly manipulated the South African state for their personal benefit – fled to Dubai after the fall of Zuma and their other political patrons in 2018.

As a result, the possibility of justice is an international question, one that South African authorities have brought to a head by seeking Interpol notices and sending extradition requests for two of the brothers, their wives, and some business associates. While the extradition requests focus on specific charges of corrupt diversion of state funds to Gupta-controlled companies through sham contracts, other notorious incidents of public concern include the Guptas’ alleged influence in the firing and hiring of key government officials and their use of a South African Air Force base to land a plane full of international guests en route to a family wedding.

South Africa’s foreign partners should want to help it protect its democracy from the corrosive effects of grand corruption. Less graft would mean greater stability, with more public funds to address systemic poverty and record-high levels of income inequality. Greater confidence in South Africa’s political system could also drive investments and economic growth, making the country a stronger trading partner. A more accountable government would serve as a powerful, positive example to South Africa’s neighbours and other countries that are also grappling with corruption.

Some countries, notably the US and UK, have recently taken valuable initial steps befitting their responsibilities as jurisdictions where corrupt actors often store their funds. The US Department of the Treasury in 2019 imposed economic sanctions on the Gupta brothers and one of their associates, stating that the family had “leveraged its political connections to engage in widespread corruption and bribery, capture government contracts, and misappropriate state assets.” (The Guptas have denied wrongdoing.) In April this year, the UK followed suit, sanctioning the Gupta brothers under its new sanctions authorities for combating corruption.

South African officials expressed their appreciation for the sanctions, which signalled diplomatic support for the country’s reforms and, more tangibly, blocked the four men from entering the US and the UK, froze any of their assets in either country’s jurisdiction, and barred US and British banks and businesses from engaging in transactions with them. While these sanctions are a powerful tool, however, they should not be an end in themselves but rather a starting point toward other forms of accountability.

In that regard, the UAE has so far appeared to be hindering rather than helping. Top South African officials have signalled that the Emiratis have handled the Guptas in a way that bears out the country’s reputation for being tight-lipped and uncooperative with foreign corruption investigations. While the UAE at last in June ratified the extradition and mutual legal assistance treaties the two countries signed in 2018, it remains unclear whether it will now extradite the accused or act on South Africa’s long-standing requests for related bank records and other evidence.

Given the full picture that has emerged regarding the Guptas’ illicit activities in South Africa, re-establishing the rule of law requires that they not remain beyond the reach of justice.

The UAE may not view the defence of democracy against corruption as a common interest, but it does have another reason to demonstrate good global citizenship: The international Financial Action Task Force will soon complete its yearlong review of the country’s flawed record and deficient systems for providing this and other kinds of international cooperation. If the review’s assessment is negative, the UAE risks the stigma of being added to the international “grey list” of states that require closer scrutiny because of their elevated risk of money laundering and terrorist financing.

Against that backdrop, the US, the UK, and India (which also received an extradition request, given the Guptas’ significant personal and economic ties there) should present a united diplomatic front in supporting South Africa.

These governments should jointly press for Emirati cooperation on corruption matters, including prompt action on requests that South African authorities have made under the relevant bilateral treaties and the UN Convention against Corruption. To increase the pressure on the Guptas, the governments that imposed sanctions could issue financial penalties against any individuals or companies in their jurisdictions that have continued transacting with them.

Western countries must do more than impose sanctions abroad to prevent and respond to corruption. For the US, that includes quickly and thoroughly implementing the new corporate transparency provisions that the US Congress adopted last year. It also includes strictly enforcing US laws to ensure that American companies that have enabled corruption abroad – as several major US consulting firms appear to have done in South Africa – are investigated and held accountable for any wrongdoing.

On top of these systemic reforms, international cooperation toward holding the Guptas accountable would send a powerful and necessary message: Governments and citizens around the world will ensure that corruption has consequences, even if the perpetrators cross a border. The stakes for democracy are too high to do any less.

Lewis is the executive director of Corruption Watch, a South African nongovernmental organisation and chapter of Transparency International working to fight corruption in South Africa. Twitter: @Corruption_SA. Breen is president and CEO of Human Rights First, a US-based nongovernmental organisation that advocates for the use of targeted sanctions and other measures to combat human rights abuse and corruption. Twitter: @M_Breen