|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Judith February

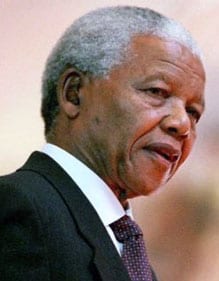

One of the defining moments of Nelson Mandela’s presidency was when he took the stand in the case of the President of the RSA and Others versus South African Rugby Football Union (Sarfu) and Others in 1999.

The year before, Mandela appointed a commission to investigate allegations of racism, nepotism and corruption against Sarfu, which approached the court in order to stop the commission’s work. Judge William de Villiers saw fit to subpoena Mandela to give evidence about why he ordered the probe.

This sparked much debate about whether the president should have to defend his every decision in a court of law. Mandela chose to do so in this case, and was subjected to a lengthy cross-examination by Sarfu’s legal counsel.

Judge de Villiers eventually ruled in favour of Sarfu, setting aside the government’s inquiry and called Mandela ‘an unsatisfactory witness’. This is an important bit of legal history.

That Mandela was prepared to place himself in such a position of scrutiny was a singular act of leadership. It not only showed his commitment to the rule of law and the constitution, but was also a visible reminder that no one, not even the president, was above the law or above being held accountable. It was an action that embedded a culture of constitutionalism during a period of intense political and social change.

That Mandela was prepared to place himself in such a position of scrutiny was a singular act of leadership. It not only showed his commitment to the rule of law and the constitution, but was also a visible reminder that no one, not even the president, was above the law or above being held accountable. It was an action that embedded a culture of constitutionalism during a period of intense political and social change.

Attacks on the judiciary are not new

The final constitution was adopted in 1996, a product of negotiations and public participation on a scale that South Africa had not experienced before. Mandela knew that a constitution could only be strong if those in power submit to it and if it transforms the lives of citizens. One must wonder what Mandela would have made of the attacks by today’s ANC leadership on the judiciary and its flouting of court orders, such as we have seen in the case of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir.

ANC Secretary-General Gwede Mantashe launched a scathing attack on the courts, calling them ‘problematic’ and saying ‘some sections’ of the court system were driven by a desire to ‘create chaos for governance’ in South Africa. His deputy, Jessie Duarte, followed suit.

But these attacks on the judiciary are not new. In 2012, while delivering a lecture in honour of former ANC president-general AB Xuma, Ngoaka Ramathlodi, the then deputy minister of correctional services, attacked the judiciary and accused it of seeking to undermine the executive. The ANC clearly feels insecure in power and it should too.

The latest Stats SA figures show the number of unemployed people is rising, especially among South African youth. In metros like Johannesburg and Nelson Mandela Bay, the ANC will come under serious electoral pressure if they do not improve their governance. In addition, South Africans seem to have lost their ability to negotiate and find a middle ground.

Parliament, so hamstrung by a partisan speaker, has failed dismally to find consensus on various issues. This has left some opposition political parties with no choice but to approach the courts for resolution on matters that the courts were not designed to address.

When the courts increasingly deal with political matters, inevitably questions will be raised about a blurring of the separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. Doing democracy in this way is tiring and time-consuming, not to mention costly. In addition, unintended consequences creep in.

Executive shows little regard for the rule of law

The Bashir case has raised some uncomfortable questions about the International Criminal Court and its mandate. Setting that specific case aside, South Africa faces a crisis when court orders are blatantly flouted. Where does that actually leave us?

President Jacob Zuma has shown little regard for the rule of law. He has consistently questioned the public protector’s recommendations on Nkandla and her authority to even make such recommendations. By his very actions, he undermines a constitutionally mandated body. What incentive might there be for government departments to adhere to court orders on implementing, for example, socio-economic rights when the executive or the ANC leadership believes it is in a position to cherry-pick which court orders it will adhere to?

Last week, a court found the directors of Aurora, including Zuma’s nephew Khulubuse Zuma, guilty of stripping Pamodzi Gold’s mines. Might Zuma’s nephew then be inclined also to ignore the findings of a court? After all, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander, right? And herein lies the danger of the impunity of the ‘Bashir moment’. Once those in power believe that the law no longer suits their purposes and that they can flout it, this might apply to all manner of things – from tax compliance by citizens, to the private sector failing to implement the laws or court orders.

Mandela recognised that the alternative to a constitutional democracy was rule by the whim of the powerful, which was anathema to the struggle for justice. It is time for the current ANC leadership to revisit the Sarfu case and its significance for present-day South Africa.

• Judith February is a senior researcher in the Governance, Crime and Justice Division, ISS Pretoria

• This article was first published by Business Day