|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

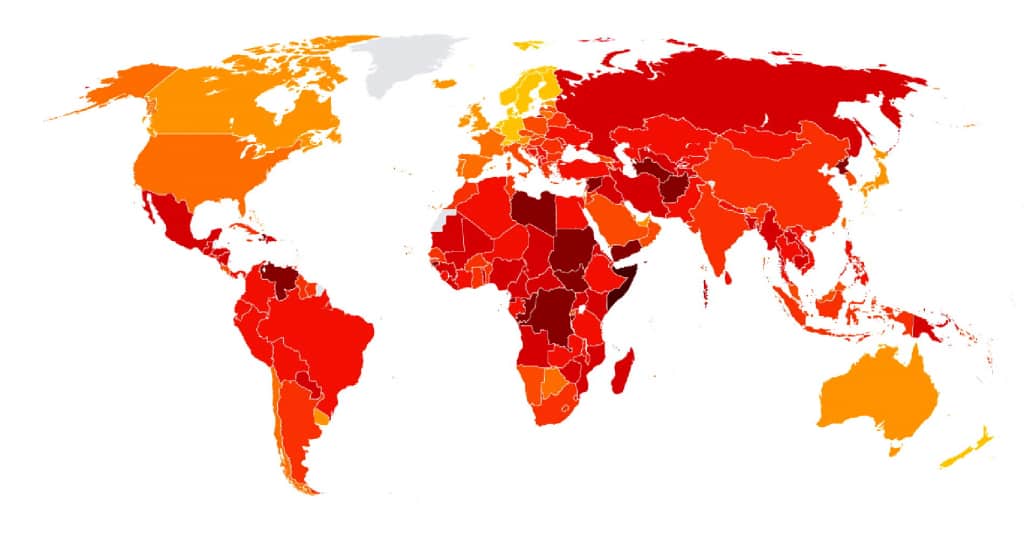

The 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), released today by Transparency International (TI), does not bring any good news for South Africans weary of the never-ending looting, incompetence and malfeasance that have characterised the country in recent years.

Using a scale of zero to 100, where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean, the CPI ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of corruption in the public sector according to experts and business people.

This year’s report focuses on the correlation between politics, money and corruption. It notes that unregulated flows of big money in politics make public policy vulnerable to undue influence.

“To have any chance of ending corruption and improving peoples’ lives, we must tackle the relationship between politics and big money,” comments Patricia Moreira, TI MD. “All citizens must be represented in decision-making.”

TI’s research shows that corruption is more pervasive in countries where big money can flow freely into electoral campaigns and where governments listen only to the voices of wealthy or well-connected individuals. Meanwhile, countries with stronger enforcement of campaign finance regulations have lower levels of corruption, as measured by the CPI.

Since 2012, only 22 countries have significantly improved their CPI scores, including Greece, Guyana and Estonia. In the same period, 21 countries significantly decreased their scores, including Canada, Australia and Nicaragua. In the remaining 137 countries – of which South Africa is one – the levels of corruption show little to no change.

Sub-Saharan Africa the weakest link

South Africa’s 2019 score is 44, an insignificant increase of one point over last year’s mediocre tally of 43. The country ranks at 70, along with Hungary, Romania and Suriname.

“A staggering number of countries are showing little to no improvement in tackling corruption. Our analysis also suggests that reducing big money in politics and promoting inclusive political decision-making are essential to curb corruption,” the report notes.

South Africa is one of the 66% of countries whose score remains below 50. As before, the sub-Saharan African (SSA) region is the worst performing, with an average score of just 32 out of 100 – far below the global average of 43.

With a score of 66, the Seychelles is impressive enough to scoop the top spot in the SSA region, followed by Botswana (61), Cabo Verde (58), Rwanda (53) and Mauritius (52). At the bottom of the index are Somalia (9), South Sudan (12), Sudan (16) and Equatorial Guinea (16).

The sub-Saharan African table reads as follows:

- Seychelles 66 27

- Botswana 61 34

- Cabo Verde 58 41

- Rwanda 53 51

- Mauritius 52 56

- Namibia 52 56

- Sao Tome and Principe 46 64

- Senegal 45 66

- South Africa 44 70

- Benin 41 80

South Africa yet again occupies the ninth slot on the SSA list.

In terms of the entire African Union, Tunisia comes in at number 10 with a score of 43 and ranking of 74, but it falls under the Middle East/North Africa region and so is not represented on the SSA table above.

Tighter controls over campaign funding is essential

TI cites data from Varieties for Democracy as showing that countries where campaign finance regulations are comprehensive and systematically enforced have an average score of 70 on the CPI. On the other hand, countries where such regulations either don’t exist or are poorly enforced score an average of just 34 and 35 respectively.

This is a telling indictment on South Africa, whose score is approaching the dismal depths of those nations whose campaign finance legislation is either non-existent or poorly enforced. The country’s long-awaited Political Party Funding Act has not yet been enacted, a full year since it was signed into law.

Of the 22 countries that significantly improved on the CPI since 2012, more than 60% (14 countries) also strengthened their enforcement of campaign finance regulations. They include South Korea and Côte d’Ivoire. Clearly, if South Africa wants to post a more respectable CPI score it will have to tackle this area, which politicians have been fiercely protecting all the while.

Recommendations

TI has issued seven crucial recommendations which, it says, will cut down on corruption and restore trust in politics by preventing opportunities for political corruption and fostering the integrity of political systems.

- Control political financing to prevent excessive money and influence in politics;

- Manage conflicts of interest and address “revolving doors”;

- Reinforce checks and balances and promote separation of powers;

- Strengthen electoral integrity and prevent and sanction misinformation campaigns;

- Empower citizens and protect activists, whistle-blowers and journalists;

- Tackle preferential treatment to ensure budgets and public services aren’t driven by personal connections or biased towards special interests;

- Regulate lobbying activities open and meaningful access to decision-making.