|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What is a commission of inquiry?

A commission of inquiry is one of many bodies available to the government to inquire into various issues. Commissions report findings, give advice and make recommendations. While their findings are not legally binding, they can be highly influential. Commissions must act strictly within their terms of reference and ensure their processes are within the law.

A commission of inquiry is established by the president in terms of the Commissions Act 8 of 1947. The president is not bound to follow the advice or recommendations of the commission; nevertheless, there would have to be good reasons why the recommendations are not taken seriously.

What is the difference between a court of law and a commission of inquiry?

Commissions are often confused with courts of law. And this can lead to unrealistic expectations. This isn’t surprising. Many commissions have been chaired by retired or sitting judges, and they also seem to function like courts. For example, affected parties are often represented by lawyers and witnesses take oaths to tell the truth.

But they aren’t courts. And it’s important to understand the difference between the two when it comes to their functions, powers, and procedures.

The differences: a court judgment is binding and has direct legal effect on the parties involved. The court will determine that the accused goes to prison, for example, or that the defendant pays damages. The only way affected parties can escape the court order is by getting it overturned on appeal or review by a higher court.

Commissions of inquiry, on the other hand, make non-binding recommendations to the person who set them up. Technically, all commissions do is offer the person who set them up advice. And they’re required to stick to the issues on which advice was requested. These are set out in the terms of reference which establish what questions the commission must answer, who will head it up and what its powers are.

Commissions of inquiry are completely different from courts when it comes to procedures too. South Africans courts are adversarial. The judge sits as an outside observer while the two teams before her attempt to establish their version of events. Commissions of inquiry, on the other hand, are inquisitorial. This makes the commission the driver of the investigation itself. It seeks out the facts rather than waiting for two opposing parties to choose and present their evidence. In an inquisitorial process, the witnesses and their lawyers are merely assisting the commission’s investigation.

An important consequence of the inquisitorial process is that a commission is not bound by the same rules of evidence as in a court. Thus, evidence will never be “inadmissible”, as the commission enjoys discretion to consider all evidence that it finds relevant to its inquiry.

Can a commission of inquiry’s findings be challenged?

Because the findings are non-binding, the findings of a commission of inquiry are generally not subject to the (higher) standards of so-called “administrative” review unless their findings have a direct effect on the persons who might want to challenge them. But the direct effect would arise only when the president acts on the findings.

Administrative review would happen under the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA). However, that applies only to administrative decisions. The president wouldn’t be subject to administrative review in many of these cases either.

What is the difference between an administrative review and a rationality review?

The president and the commission are however subject to review for “rationality”. A rationality review asks only whether there is a rational connection between the conduct challenged before the court (or commission) and a legitimate governmental objective.

So, what then is the value of a commission of inquiry?

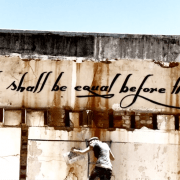

Commissions have a crucial function: to surface evidence and thereby to educate the public and ensuring its buy-in for important processes of change and renewal. Through having open hearings, broadcast publicly, public access (such as a website and an enquiry desk) and a strong, independent commissioner, a good commission can reaffirm the public’s faith in the principle of accountability, and in the structures and institutions set up to enforce those (Constitutional) principles.

Given our collective faith in the independence of the judiciary, how a judge (appointed as a commissioner) handles the process can either strengthen or weaken the public’s faith in the government of the day.

This is where the judicial procedure comes in. Although it can render the body less accessible, it does have the strong advantage of satisfying people’s innate sense of natural justice. And the decisions of the commissions will only have legitimacy in the eyes of the public if they are seen to treat people fairly. That is one of the reasons why implicated people need enough time to respond to the allegations against them.

What was the arms deal?

In 1999, the South African government signed the final contracts for the Strategic Defence Procurement Package (SDPP), better known as the “arms deal”. This deal saw South Africa purchase a number of weapon systems, including naval ships, submarines, helicopters and aircraft for use by the South African Defence Force.

From the word go, the arms deal was embroiled in allegations of corruption and fraud. Questions have also been raised regarding its usefulness, particularly due to the lack of any substantial military threat against South Africa after 1994. Concerns were heightened given South Africa’s innumerable social problems that many have argued were in higher need of the resources that were diverted to the procurement of arms.

In 2011, Terry Crawford-Brown approached the Constitutional Court in a bid to force President Jacob Zuma to set up a commission of inquiry into the procurement packages and allegations of criminal misconduct resulting from it. The president settled before the matter could be heard in court and agreed to set up the arms procurement commission

When was the Seriti Commission established?

The commission was set up in 2011 by then President Jacob Zuma, who appointed Judge Willie Seriti, a justice of the Supreme Court, to head the probe. Seriti was to be flanked by judges Willem van der Merwe and Francis Legodi, both of whom resigned before hearings began. He was then assisted by Judge Hendrick Musi, judge president of the Free State High Court, who was appointed after Van Der Merwe left. Justice Legodi was not replaced. The commission had to overcome a few stumbling blocks – a senior investigator and a law researcher also quit before proceedings had even got under way, and the commission’s secretary, a top attorney, was found dead, apparently by his own hand, in his car in KwaZulu-Natal in 2012.

What were its terms of reference?

The commission investigated “allegations of fraud, corruption, impropriety or irregularity in the strategic defence procurement package”. It was meant to question the rationale for the Arms Deal, whether the equipment purchased is adequately used or not, and whether job opportunities linked to the arm deal have materialised or not – among other tasks. Allegations were levelled against suppliers as well as those on the procurement side.

The Seriti Commission had the following terms of reference:

The Commission of Inquiry shall inquire into, make findings, report on and make recommendations concerning the following, taking into consideration the Constitution and relevant legislation, policies and guidelines:

1.1. The rationale for the SDPP.

1.2. Whether the arms and equipment acquired in terms of the SDPP are underutilised or not utilised at all.

1.3. Whether job opportunities anticipated to flow from the SDPP have materialised at all and:

1.3.1. if they have, the extent to which they have materialised; and

1.3.2. if they have not, the steps that ought to be taken to realise them.

1.4. Whether off-sets anticipated to flow from the SDPP have materialised at all and:

1.4.1. if they have, the extent to which they have materialised; and

1.4.2. if they have not, the steps that ought to be taken to realise them.

1.5. Whether any person/s, within and/or outside the Government of South Africa, improperly influenced the award or conclusion of any of the contracts awarded and concluded in the SDPP procurement process and, if so:

1.5.1. Whether legal proceedings should be instituted against such cancellation, and the ramifications of such cancellation.

What were the findings of the Seriti Commission?

In reporting on the findings of the commission, former President Zuma said the Commission had concluded that there was no room for it to “draw adverse inferences, inconsistent with the direct, credible evidence presented to it”. Further, “government had been of the view that any findings pointing to wrongdoing should be given to law enforcement agencies for further action. There are no such findings and the commission does not make any recommendations

The commission’s six findings are as follows:

1. Did any person or persons improperly influence the awarding or conclusion of any of the contracts?

The commission found that the evidence presented before It does not suggest that undue or improper influence played any role in the selection of the preferred bidders, which ultimately entered into contracts with the government.

2. Was any contract concluded through the arms deal tainted by any fraud or corruption?

According to the commission, widespread allegations of bribery, corruption and fraud in the arms procurement process, especially in relation to the selection of the preferred bidders and costs, had found no support or corroboration in the evidence, oral or documentary, placed before it. There was also no evidence found through the commission’s own independent inquiries.

According to the commission, large payments made to consultants gave an impression that the money may have been destined for decision makers in the arms deal, and that they may have been bribed. The fact that some consultants knew or had personal contact with senior politicians in government was also cited as corroboration.

“The commission states that not a single iota of evidence (emphasis added) was placed before it, showing that any of the money received by any of the consultants was paid to any officials involved in the strategic defence procurement package, let alone any of the members of the inter-ministerial committee that oversaw the process, or any member of the Cabinet that took the final decisions, nor is there any circumstantial evidence pointing to this.” (Zuma).

“The commission states that the preferred bidders confirmed that the money was for the consultant’s services and nothing else.”

Some of the individuals implicated in the allegations of wrongdoing testified during the commission and denied the allegations. They include former president Thabo Mbeki, and former ministers Trevor Manuel, Alec Erwin, Mosiuoa Lekota and Ronnie Kasrils. The commission found that none of them had been discredited as a witness.

Other than the Lead-in Fighter Trainer (LIFT) programme, the inter-ministerial committee had accepted, unaltered, the results of the evaluations produced by the technical teams and recommended to the full Cabinet, and the preferred bidders identified by the technical evaluations, according to the commission. Where it had taken a different decision, it had given full reasons.

Moreover, the commission said there was no evidence that such decision was tainted by any improper motives or criminal shenanigans. There was also no basis whatsoever for disbelieving the evidence submitted by the members of the Inter-Ministerial Committee in this regard.

3. Did the off-sets anticipated to flow from the arms deal materialise?

Zuma said the commission found that it was fair to conclude that the anticipated offsets had substantially materialised. “Adequate arrangements are in place to ensure that those who have not met their obligations, do so in the immediate future,” he said.

4. Did the country need the arms deal?

Zuma announced that the commission had found that the strategic defence procurement package was needed. “[It found that] it was necessary for the South African National Defence Force to acquire the equipment it procured in order to carry out its constitutional mandate and international obligations of peace support and peace-keeping,” he said.

5.Were the arms and equipment acquired underutilised or not utilised at all?

The commission found that all the arms and equipment acquired were well utilised.

6. Did job opportunities anticipated to flow from the arms deal materialise?

According to the commission, the evidence tendered before it indicated that the projected number of jobs to be created was achieved. “The commission states that the probabilities are that the number of jobs created or retained would be higher than 11 916,” said Zuma.

Why are you challenging the findings?

The Commissions Act requires a commission of inquiry not simply to listen to the evidence before it but to go out and investigate the matter in an inquisitorial sort of way. And it hasn’t done that. It simply relied on evidence that was presented to it, and has taken that evidence in a very questionable, selective manner. The commission actively ignored or excluded evidence. The procedures adopted by the commission where highly questionable; they were deeply flawed and deeply irregular.

But even more than that, notwithstanding that there had been two criminal findings in the courts of law, in relation to corruption in the arms deal, the commission found nothing untoward. We’re arguing in the first instance that they haven’t done what a commission is mandated to do. But there are also administrative grounds for setting it aside. The way in which evidence was gathered, the way in which certain evidence was ignored, the way in which witnesses were not given access to certain of the evidence presented to the commission.

What will be the effect of setting aside the findings?

If the commission’s report is set aside, no-one will be able then they will no longer stand as a judicial finding on whether or not there was corruption involved in the arms deal. We think that’s important in and of itself. As things stand at the moment the commission has exonerated those Involved in the arms deal from any corrupt conduct. We believe pretty firmly that that is not a credible finding.