|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Tara Davis

First published on Etico

The idea that education is the key tool to alleviating poverty may be reductionist, but it’s not wrong. Education has the potential to create economic opportunities and upward social mobility.

It is a particularly important tool in South Africa where there is an urgent need for access to redress, where the class divide seems ever-broadening and where the realisation of socio-economic rights is slow. Its importance is recognised in section 29 of our Constitution as an immediately realisable right, and one not limited by a ‘within available resources’ caveat. The right extends beyond an obligation to merely provide access to education – it includes the duty to transform, as a matter of urgency, South Africa’s historically unequal and inadequate education system.

Since our launch in January 2012, Corruption Watch has received over 26 000 reports from members of the public alleging corruption. Reports are collected through various platforms – among others, we have a secure website report form, a dedicated corruption hotline and WhatsApp number, an SMS callback service, and we also invite the public to come to our offices to talk with us about their experiences. Out of those 26 000+ reports, 22% relate to allegations of corruption and maladministration in schools; this makes it the sector most consistently reported on.

The most frequent types of corruption reported within schools include the embezzlement of funds, mismanagement of funds, employment irregularities and irregularities in procurement. For instance, at one particular school, our investigation found that between 2008 and 2010 a total of 503 cheques were issued by the school. Of those, 362, valued together at over R1.5-million, had no supporting documentation, while some funds were never deposited into the school’s bank account. At another school, a principal was alleged to have handed out jobs to family and friends, siphoned R2-million from a school fund, and waived school fees for some pupils.

Our 2018 Analysis of Corruption Trends Report highlighted the persistent involvement of school principals, teachers and school governing bodies in corrupt practices. It also revealed a concerning increase in sextortion cases – allegations which involve educators soliciting sexual favours from learners in exchange for higher marks or promotion to the next grade.

The pervasive nature of corruption in our school system undermines the achievement of the right to education, the consequence of which is borne by learners every day when they attend schools with crumbling infrastructure, squeeze into make-shift classrooms and share textbooks – if they have any at all.

Accordingly, Corruption Watch has been engaged in untangling corruption in the education sector for over seven years. Our strategy has been multifaceted and recognises the importance of a holistic approach. We investigate certain allegations of corruption and, despite our limited powers, attempt to resolve them – some of these investigations can be viewed here.

We use the anecdotal evidence obtained from these reports to inform legislative and policy recommendations – we are currently working on a report in partnership with The South African Human Rights Commission. This report will examine accountability and governance regimes in the country’s education system and, by identifying gaps in the national and provincial legislative framework, will make recommendations on how to strengthen these systems and utilise them most effectively.

Our schools campaign, launched in 2013, is our longest running campaign. It has involved various activities that target school governing bodies and learners. We have focused strongly on capacity building in schools across the country to enable oversight bodies to exercise their function effectively. This was achieved through the development and distribution of various tool-kits and handbooks that provide guidance on how the school system should operate and what to do when it doesn’t.

An example of one of our focused school interventions is the campaign we conducted around the school governing body (SGB) elections in 2015 and 2018. Held every three years, this is South Africa’s third biggest public election after national and local government elections. For the 2018 SGB elections, we strategised with the Department of Education and mounted efforts to increase public participation and transparency in the election process. Among other initiatives, we updated our 2015 SGB handbook which explains the duties and responsibilities of SGB members and how to hold education authorities accountable, we launched a donations campaign encouraging people to support us in striving for good governance in schools, we published articles and op-eds on the topic on our website and in the media, and we conducted awareness workshops and shared relevant information from the Department of Education.

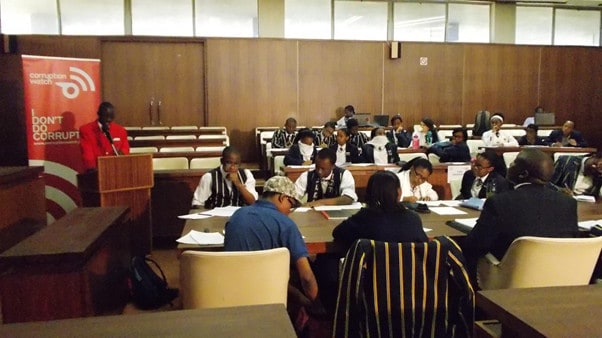

Our work with learners focuses on building awareness. For example, we engaged various schools by hosting a debate with the motion: “this house believes that teaching public ethics in all secondary schools will combat corruption.” We also conducted workshops with student representative councils in order to help them understand their rights and the role they could play in promoting transparency and accountability.

The receipt of hundreds of new reports of corruption each year forces us to confront the reality that resolving the issue of corrupt practices within the education sector is slow. It is easy to become immobilised in the face of such apathy, but we have worked with hundreds of individuals and learners who continue to fight for the achievement of the right to education. These are the individuals who have inspired our interventions for over seven years and whose persistence and tenacity have encouraged our own.

Tara Davis is an attorney at Corruption Watch with a particular interest in education and procurement.