|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Karam Singh and Tharin Pillay

First published on News24

Corruption Watch opened its doors 10 years ago on 26 January, to a warm reception from the media and government alike. The organisation’s primary aim is to facilitate public participation by providing citizens with a platform where they can report experiences of corruption.

On this front, we have been successful: more than 35 000 whistleblowers have submitted reports to us, and these reports have formed the basis of our work in identifying corruption hotspots, conducting research and investigations, and developing targeted mobilisation campaigns.

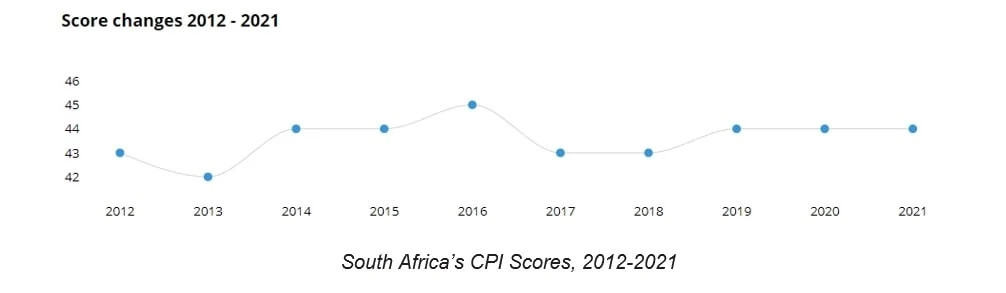

But while the last decade has been kind to Corruption Watch, which also serves as the South African chapter of global anti-corruption movement Transparency International, it has been catastrophic for South Africa. Our country has stagnated in its efforts to fight corruption, as evidenced by data from Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

The CPI scores 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. Scores are given on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) and calculated by aggregating survey and assessment data from an array of reputable institutions. South Africa has received a score of 44/100, for the third year in a row. In the last decade, our score has flitted between 42 and 45.

None of this is news. Stories about public sector corruption – about billions of rand stolen through the abuse of tender processes, Gupta-driven cadre deployment, and flagrant law-breaking by politically-connected elites – have dominated headlines every week for well over a decade. Meanwhile, the country’s most vulnerable citizens have borne the costs as they have been deprived of the goods and services, like water, electricity, education, and functional transport infrastructure, to which they are constitutionally entitled.

Those who have dared to stand up to and call out this criminality have been met with threats, intimidation, and violence. They have paid with their careers, their peace of mind, and in some cases, their lives.

Given that those in power have shown total disregard for human rights by looting the public purse, it is not surprising that South Africans’ trust in state institutions and political parties is reaching new lows. As a country, we are in a dangerous place.

And while we are starting to find some answers about how these crimes were perpetrated – for example, via the excellent investigative work of the Zondo Commission and the Special Investigating Unit – it does not look like much is changing. Despite promises that President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ascent to power would usher in a “new dawn“, the siphoning of public money for private interests has continued, largely unabated, throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. State capture continues.

The problem is not that we lack solutions. Putting aside the necessity of timeous prosecutions, there are a variety of changes to South Africa’s anti-corruption policy framework, which could be made in a short period of time, and which could bring about dramatic improvement. For example:

- Public procurement data could be made publicly available on a permanent basis, as the National Treasury has done with Covid-19-related procurement data.

- The public procurement legislative framework, which is currently sprawling and fragmented, could be consolidated and simplified.

- Require disclosure and establish a database for beneficial ownership transparency, such that investigators can discern for whom front companies operate.

- Incentivise whistleblowers to make disclosures by offering a proportion of the money recovered in litigation if their disclosure leads to a conviction, as is done in e.g. the United States and South Korea.

- Indemnify whistleblowers from criminal/civil litigation, and provide them with greater protection and assistance from the government.

- Establish an independent agency to, among other things, receive and investigate whistleblower complaints, in line with international best practice.

The problem is not even that the government is unaware of these solutions. In November 2020, Ramaphosa released the National Anti-Corruption Strategy 2020-2030 (NACS), which identifies six pillars that should undergird the country’s approach to tackling corruption. In early January Part 1 of the Zondo report was released, with its own set of proposed policy reforms – notable among them the call for an agency dedicated to anti-corruption in public procurement. Part 2 of the Zondo report, released this week, details how billions of rand were extracted from Transnet and Denel.

The problem is that, for all the incumbent government’s rhetoric on transparency, accountability, and consequence management, little has been done to implement these solutions. For example, the first step in implementing the NACS is to establish an interim “National Anti-Corruption Advisory Council”, which has yet to happen, despite Ramaphosa’s promise that this would be established by mid-2021. This points to a deplorable lack of political will. This lack of political will is understandable – given that corrupt people in power have everything to lose if anti-corruption efforts succeed – but it is deplorable nonetheless.

As the NACS itself notes, a “whole-society” approach is necessary to fight corruption. Corruption Watch, and civil society more broadly, has been tireless in its efforts to push for transparency and to hold leaders to account. Similarly, groups that represent business interests, like Business Leadership SA and Business Unity SA, have committed themselves to anti-corruption. We must be mindful, though, of the role of actors in the private sector – particularly lawyers, accountants, and consultants – in enabling widespread corruption.

Solutions are on the table, and the rest of society stands ready to support and to implement them.

The onus now is on the government to show courage and leadership by moving beyond hollow promises and towards concrete action. Expedite the creation of the NACS Advisory Council. Set up committees in Parliament to draft white papers to give effect to procurement reform and whistleblower protection recommendations. Show South Africa that change is possible, that a government can act quickly and authoritatively when it is serious about the interests of its people.

Social order is a fragile thing. As last year’s July riots made clear, it can shatter overnight. With authoritarianism and xenophobia on the rise globally, and with democracy and human rights under increasing threat, we seem to be fast approaching a turning point in our democratic history. South Africa may not survive another decade of state capture. If our citizens’ trust in the country’s democratic institutions falls much further, any number of dystopian futures may await us.

The window of opportunity to intervene may soon close. We cannot wait any longer. Government must take meaningful action now.

– Karam Singh is the executive director at Corruption Watch, and Tharin Pillay is a legal researcher at the same organisation