|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By David Lewis

First published in Daily Maverick

Ranjeni Munusamy poses a pertinent question when she asks “Is South Africa losing its activism mojo?”. And, cited in the same article, Zwelinzima Vavi answers this in the affirmative when he says: “South Africans have become resigned. They are complaining everywhere but there is no real activism. That is a great concern, that people are happy to do nothing when corruption has reached the levels it has in our society.”

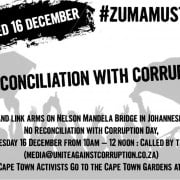

Both agree that the coming anti-corruption marches scheduled to take place in Pretoria and Cape Town on 30 September are an important test of civil society’s mojo.

Corruption Watch’s experience belies the notion that South Africans have lost their taste for activism, at least in relation to corruption. There has been a very powerful public response to our work, whether measured by the volume of whistleblowing reports that we receive, or by the character and intensity of many conversations on radio call-in shows, or by mainstream and community media coverage, or by readership of our website, or by our following on social media, or by the responses of key stakeholder groups to our schools, youth and migrant and refugee campaigns.

I’m aware that these may not be the measures traditionally used to gauge levels of activism. But that may well be because our measures and understanding of what constitutes activism need to reflect 2015 rather than 1990, but more of that later.

There is, to be sure, a large measure of complaining in the responses to corruption. But that’s not new or a unique response to corruption and nor is it to be discounted as a form of activism. What is true, is that people are confused about what is to be done about corruption. And nor can they be blamed for that. We are dealing with a multi-headed monster that is pervasive, systemic and replete with grey areas. But what is equally true, is that there is no basis for claiming that South Africans have resigned themselves to corruption. We may be in danger of getting there; but we’re not there yet.

Civil society action not as efficient since democracy

But all that having been said, there is no doubt that post-democracy civil society organisation has generally been considerably weaker and less active than its pre-democracy counterpart, and certainly if measured by the volume and character of the mass action that characterised the 1970s and 80s. There are of course significant exceptions to this generalisation, with the Treatment Action Campaign and the Right2Know Campaign standing out. It is important to appreciate that these campaigns were most successful when focused on a single issue. This focus is very much more difficult to achieve when a deeply systemic and all-pervasive issue like corruption is the object of popular mobilisation.

Some may point to the high and growing incidence of service delivery protests as evidence of a still active civil society. But, if anything, this proves the opposite. It is, to be sure, evidence of the willingness of desperate people to put themselves on the line. But the fact that each of these acts of militancy is characterised by their isolation from other similar struggles, demonstrates the weakness of civil society organisation, the incapacity to join up and give national expression and programmatic coherence to an isolated outburst of militancy.

At first blush, the post-democracy decline of civil society is puzzling. After all, the increasing hostility of the government notwithstanding (I can’t recall even an apartheid minister referring to civil society as a “disease”, the epithet recently used by Blade Nzimande), there can be no doubt that the space for civil society organisation is significantly greater now than under apartheid.

But that greater space may be one of the causes of a perceived decline in activism. Certainly, greater access to sympathetic courts and, above all, a supportive constitution, has shifted the terrain of activism from the streets to the courts, even though the Treatment Action Campaign/Aids Law Project model clearly demonstrates that court gains are most likely to be sustained when combined with popular mobilisation.

The advent of democracy has also impacted on the ease of access that civil society organisations have to funding. Aid funding is no longer as readily accessible and philanthropic money is, for a variety of reasons, tight. The organisation of the anti-corruption march has been severely hampered by funding constraints for everything from the provision of buses to the provision of toilets. And, of course, the one component of civil society that has access to funding – the unions – is sharply divided, not least because it has become a battleground for access to the huge resources which the unions command.

The state of the unions – and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in particular – is a major factor accounting for the weakness of civil society. The anti-corruption march will be the first such event in some 35 years that, thanks to the searing divisions in Cosatu, cannot rely on the most militant section of the union movement to bring out its members. The National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa is committed to the march but it is fighting battles on a range of fronts – within the union movement, with the African National Congress and in the workplace, where it is faced with the spectre of massive retrenchments, the most difficult conditions for union militancy.

South Africans are still committed to activism

And so, has South Africa lost its activism mojo? And will the anti-corruption marches provide, one way or another, a definitive answer to this question?

I don’t think South Africans have turned their backs on social activism. But I do think civil society organisation – critically including the faith-based organisations – is emerging from a long post-1994 slumber. And there can be no doubt that organised labour’s ability to engage in coherent, disciplined mass activism is weaker now that at any point since the late 70s.

Civil society’s long sleep was induced by a range of factors. Paradoxical though it may seem, the triumph of democracy is clearly one factor. In the immediate aftermath of the 1994 transition, the leadership of civil society decamped in favour of employment in the government and leading positions in the ruling party. Having achieved the reins of political power, they (myself included) headed for the government both to deliver the fruits of democracy to their erstwhile constituencies, as well as to enjoy its fruits in the shape of well-paid and powerful jobs in the relatively well-resourced public service. To their constituents they effectively said “we will go to Pretoria and bring back your due rewards to you”. But though some promises were honoured, others were clearly not. Both the leadership and the rank-and-file of civil society organisation forgot that government, any government, is only as good as those whom it serves are demanding.

There has been a seismic shift in the modality of popular activism. To eschew use of the courts as instruments of social justice and redress would be crazy; it would be tantamount to denying the fruits of victory against a system fundamentally opposed to the rule of law. But it is undoubtedly demobilising, if mobilisation is only measured by the volume of activism on the streets. But then again, surely one of the fruits of victory against an autocratic system is precisely that conflicts, including social conflicts, do not always have to be resolved on the streets.

It’s not often remembered that anti-apartheid mobilisation was achieved without cellphones, let alone social media. These technologies undoubtedly ease the ability of civil society activists to communicate with their constituents. But they also allow ordinary people to be mobilised in their homes. To engage in activism, it is no longer necessary to attend meetings in inhospitable community halls. And the communications platforms don’t lend themselves to long, turgid manifestos. Political communication and mobilisation has to express itself in short, concise messages, most often received by those at whom they are directed in the isolated confines of their homes.

Response to societal issues must move with the times

South African civil society activists need to grasp this nettle. And right now, there is limited evidence that they are doing so. Every aspect of organisational work – from our logos to the communications platforms that we use – needs to reflect where we are today. Constantly invoking an idealised past and the memory of leaders who are no longer with us, many of whom have not been with us in the lifetimes of 30-year-old South Africans, no longer resonates. History is important but it doesn’t serve to mobilise social activism. Engaging with contemporary culture, contemporary icons, contemporary concerns, is what is needed in order to mobilise people in the here and now. Just as so many of our social problems are a legacy of our past, so too is our social activism a prisoner of our struggle against that past.

This doesn’t mean the street is no longer a terrain of social activism. Much less does it diminish the importance of public participation in civic life. But its character has to reflect contemporary circumstances. And this not only in political messaging and the adoption of new communications technologies, but in the very content and shape of mobilisation. The utilisation by groups like Equal Education of social audits, of evidence-based activism that is rooted in public participation; the Khayelitsha policing inquiry, a process that drew on many of the rules and practices of orthodox commissions of inquiry, until one went there and saw who was in attendance, saw whose concerns and needs dominated that discourse. These – and there are many other examples – suggest South Africa has not lost its activist mojo, but rather that it is struggling to find the form of social activism in the changed circumstances of 21st century South Africa.

Will the marches accurately represent our current mojo? Yes and no. There may be fewer people on the streets than was the case in a typical may-day rally in the ‘80s. But there will be a great many more people engaged in their homes and workplaces and schools, some at great physical distance from Pretoria and Cape Town, than would have been the case 30 years ago.

Mostly, I think the march will reflect how well or otherwise activists have adjusted to radically changed circumstances. And, included in these circumstances is the precipitous decline of the unions as bulwarks of social activism. That fact alone, marks this off as a new era in activism.

The street is, to be sure, important. And disciplined social activism has to reclaim it. Recent instances of street activism such as the anarchic, chaotic union marches and the conduct of the school learners in Pretoria recently have, if anything, discredited street activism and turned off ordinary South Africans. Others – Brazilians, Guatemalans, Malaysians, French – have managed. We need to do so as well. But first we have to cast off the outdated hand of the past.