|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Image: Voice of America

Global freedom of information watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF) released its 2025 World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) on 2 May 2025, and the picture it paints is not a pretty one.

The report describes a marked deterioration of press freedom around the world, with violations such as physical attacks, restricted public funding, and economic pressures contributing to the current state of affairs.

The WPFI is compiled from the organisation’s own assessment of countries’ press freedom records in the previous year. Its goal is to compare the level of freedom experienced by journalists, media, and internet users in 180 countries and territories, says RSF, using the following definition of press freedom:

“Press freedom is defined as the ability of journalists as individuals and collectives to select, produce, and disseminate news in the public interest, independent of political, economic, legal, and social interference and in the absence of threats to their physical and mental safety.”

As this definition hints, the scores are evaluated against five distinct categories or indicators: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context, and safety. The methodology involves two components on which scores are calculated – a quantitative tally of abuses against media and journalists in connection with their work, and a qualitative analysis of an RSF questionnaire (available in 25 languages) filled in by press freedom specialists in each country, such as journalists, researchers, academics, and human rights defenders.

The scores are then presented on a scale of 0 to 100, where 100 indicates the highest possible level of press freedom and 0 the lowest.

This year’s WPFI shows that global press freedom has fallen to an all-time average low score of 54.7, down from last year’s average of 55.9. RSF’s journalist barometer shows that 15 journalists have been killed since January 2025, and 561 journalists or media workers are in detention at the time of writing.

Press freedom against corruption

The media plays a vital role in exposing and controlling corruption. It not only raises public awareness about the causes and consequences of corruption, as well as the possible remedies, but it uncovers domestic and cross-border corruption through investigative journalism, acts as a watchdog by scrutinising government actions, policies, and decisions, and demands transparency and accountability by creating public pressure on officials and private companies.

For this role to be as effective as possible, media must be independent and able to operate without undue influence from government or other powerful actors. Access to information and freedom of expression are other crucial resources for holding power to account, and for acting as a voice for minorities and groups facing neglect or discrimination.

In addition, a free press provides reliable information about the state of the nation, facilitating free and open dialogue about developments and situations, and empowering voters to vote, with informed authority, for the changes and the representation they want.

It stands to reason, then, that effective media coverage must be allowed for the press to be able to carry out these important functions. But in 137 of the 180 countries on the WPFI, the state of press freedom is classified as ‘problematic’, ‘difficult’, or ‘very serious’. Only 43 countries are classified as ‘good’ or ‘satisfactory’ – South Africa sits in this group.

Financial hardship vs editorial integrity

A particular point of concern is what RSF describes as economic pressure – caused by unstable and opaque financial conditions, ownership concentration (where media ownership lies in the hands of a few people or is controlled by the government), pressure from advertisers and financial backers, and public aid that is restricted, absent, or allocated in an opaque manner, among other reasons.

“Of the five main indicators RSF uses to determine the World Press Freedom Index rankings, the indicator that measures the financial conditions of journalism is at its lowest point in history,” says the organisation.

“The data measured by the RSF Index’s economic indicator clearly shows that today’s news media are caught between preserving their editorial independence and ensuring their economic survival. Without economic independence, there can be no free press. When news media are financially strained, they are drawn into a race to attract audiences at the expense of quality reporting, and can fall prey to the oligarchs and public authorities who seek to exploit them.”

And when journalists are impoverished, says RSF editorial director Anne Bocandé, “they no longer have the means to resist the enemies of the press – those who champion disinformation and propaganda.”

RSF’s data also shows that in 160 out of the 180 countries assessed, media outlets achieve financial stability “with difficulty” – or “not at all.”

The organisation singles out the US for ongoing and rapidly declining press freedom and an increasingly hostile environment for independent journalism. That country’s rank is 57, falling into the ‘problematic’ band, with a score of 65.5.

“President Donald Trump’s second term has already intensified this trend as false economic pretexts are used to bring the press into line. This led to the abrupt end to funding for the US Agency for Global Media, which affected several newsrooms – including Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — and, as a result, over 400-million citizens worldwide were suddenly deprived of access to reliable information. Similarly, the freeze on funding for the US Agency for International Development halted US international aid, throwing hundreds of news outlets into a critical state of economic instability and forcing some to shut down – particularly in Ukraine (ranked 62).”

Bocandé says: “The media economy must urgently be restored to a state that is conducive to journalism and ensures the production of reliable information, which is inherently costly.”

Africa and South Africa

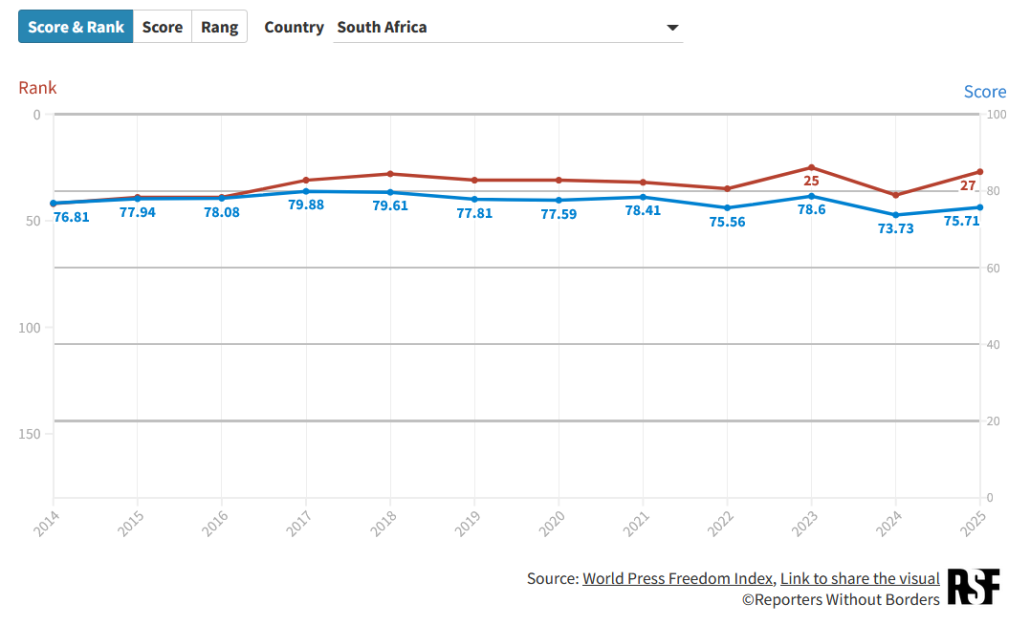

South Africa sits at 27 in the rankings, with a score of 75.7 out of a possible 100. It has improved significantly on its 2024 rank of 38 and score of 73.7, and is the highest-ranking and highest-scoring African country, followed by Namibia (28) with a score of 75.4, Cape Verde (30) with a score of 75, and Gabon (41) with a score of 70.7. These four countries fall into the ‘satisfactory’ band, and they are the only African countries which can boast this achievement.

Generally though, the African continent is not a place where media freedom thrives, nor indeed, the media houses themselves. This WPFI edition shows that Africa is home to the highest number of countries with declining economic indicators, says RSF – 80% have seen their economic scores drop.

Furthermore, “In many cases, media ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few private groups close to those in power and individuals with political interests, which compromises newsrooms’ editorial independence.”

This concentration, says RSF, is particularly notable in countries such as Nigeria (ranked 122), Sierra Leone (56), and Cameroon (131). “The issue is compounded by news outlets’ dependence on advertising revenue, which generally comes from the communication budgets of the state and major corporations … This can push newsrooms to self-censor for fear of losing funding, a concern that is not unfounded: in Kenya (117), for example, the telecom company Safaricom pulled its advertisements from The Nation after the newspaper exposed the company’s role in surveilling citizens’ communications.”

Seven sub-Saharan African countries are now in the bottom quarter of the WPFI. They are Somalia (136), Uganda (143), Ethiopia (145), Rwanda (146), Sudan (156), Djibouti (168), and last-ranked Eritrea (180).

“Informing the public is becoming a daily challenge in Africa, yet higher-ranking countries such as South Africa, Namibia, Cape Verde, and Gabon provide rays of hope.”