|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Tara Davis and Deborah Mutemwa-Tumbo

First published in the Sunday Times

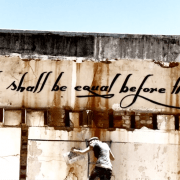

What is the point of commissions of inquiry? Are they powerful tools for investigating issues of public concern that can ultimately bring about justice, or are they expensive political options used by those in power to pacify the public and justify impunity?

Corruption Watch and the Right2Know Campaign have grappled with these questions for years. The battle to have them answered finally came before a court in mid-June, in the matter against the President of the Republic of SA and Others.

Our organisations seek to set aside the findings, released in 2016, of the arms procurement commission (Seriti commission). This commission, tasked with investigating allegations of corruption, fraud and impropriety in the strategic defence procurement package, or arms deal, surprisingly found that the entire deal was legitimate in its conception, execution and economic impact.

We disagree, and we have not let the issue go. Here is why:

Guns

On 4 December 1999 the government publicly broke the news of the arms deal, which involved the purchase of a number of weapons systems (including the three infamous submarines). It was promised that the deal would to involve an investment in our economy of up to R110-billion and create 65 000 jobs. At the time of the announcement it was estimated that the arms deal would cost the South African taxpayer a mere R30-billion — but by 2018 it had already cost us R65-billion, and payments are expected to continue up until 2022.

Controversy has pervaded the deal right from the start, for the following reasons:

- There have been sustained allegations of fraud and corruption in the contracts;

- Evidence suggests that attempts by the authorities to investigate the arms deal have been interfered with; and

- Given the socioeconomic needs of the South African population, coupled with the under-utilisation of the arms, the deal was an unnecessary waste of money.

Lies

In 2011, following sustained public outcry, former president Jacob Zuma, who himself was implicated in the alleged corruption, established the commission. Headed by judge Willie Seriti, the commission was tasked with investigating allegations of fraud, corruption, impropriety and irregularity in relation to the arms deal. The terms of reference further required a probe into the rationale for the deal, whether the arms acquired were utilised, and whether the promised job opportunities ever materialised.

The final report found that there was nothing wrong with the arms deal, all the expectations had been met, and “there [was] no need to appoint another body to investigate the allegations of criminal conduct, as no credible evidence was found during [the commission’s] investigations or presented to the commission that could sustain any criminal conviction”.

It took the commission four years to come to these findings at a further cost of R137-million to us.

The public did not accept these findings, and neither could we.

Politics

A national commission of inquiry, established in terms of the 1947 Commissions Act, can be a powerful tool to uncover truth in the murkiest of waters. It is uniquely placed to investigate matters of public concern, and while the findings are not binding, if treated seriously by the executive such findings can precipitate criminal investigations, fight impunity and bring about accountability.

Sadly, this is not what happened with the Seriti commission.

Instead, its nonbinding yet far-reaching findings were used by the “powers that be” and alleged culpable individuals to justify their impunity and avoid accountability.

This was a miscarriage of justice in the truest sense, and that is why we continue our fight. Our submissions to the court are that the commission failed to carry out its statutory duty. It did not investigate the matters within its terms of reference with an open and inquiring mind and consequently failed to investigate the matter competently.

This is clearly seen in its failure to investigate material matters, to call relevant witnesses, to admit into evidence or properly investigate highly relevant material, and to test the veracity of witness testimony. It is our view that the commission in fact obstructed and impeded a full ventilation of the issues.

Our hope is that the court will set the findings aside, as a matter of principle, and provide some much-needed guidance on how commissions of inquiry should, or at least should not, be conducted.

This could have a significant impact on restoring public trust in commissions of inquiry and the valuable role that they can play in addressing injustice.

Davis is an attorney, and Mutemwa-Tumbo is head of legal and investigation, both at Corruption Watch.