|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Back in January 2014, the Competition Commission began a market inquiry into the situation in South Africa’s private healthcare sector, with former chief justice Sandile Ngcobo presiding. The inquiry was scheduled to end in December 2015, but only recently, in September 2019, did the panel release its 280-page final report.

The reason for the long delay in finalising the process was because some private hospitals, who objected to the inquiry, took legal steps against it.

The healthcare market inquiry (HMI) was to probe the general state of competition in the market with the aim, among others, of increasing transparency, because the commission had “reason to believe that there are features of the sector that prevent, distort or restrict competition”.

The HMI took place in terms of Chapter 4A of the amended Competition Act of 1998 and, as the commission stated, in keeping with the purpose and functions of the commission set out in sections 2 and 21 of the Act respectively. These enable the commission to conduct market inquiries in respect of the “general state of competition in a market for particular goods and services” without digging into the conduct of any particular firm, and to “implement measures to increase market transparency”, among others.

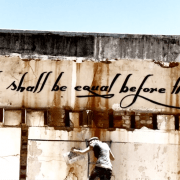

As per Section 27 of South Africa’s Constitution, everyone has the right to have access to healthcare services. Accordingly, the HMI would also determine how the market sets its prices, and ensure that the market allows for citizens’ constitutional right to access to healthcare.

Corruption Watch worked with SECTION27 as co-convenor of the civil society forum into the inquiry.

Download the full report | Download the executive summary | Download the recommendations

Parliament briefed

In March this year members of the panel, including Ngcobo, briefed the parliamentary committee for health on the findings and recommendations.

The health committee heard that the situation in the private healthcare market is marked by high and rising costs and over-utilisation, according to the HMI’s findings. Stakeholders, meanwhile, have not been able to demonstrate associated improvements in health outcomes.

Furthermore, the private healthcare market is subject to distortions which adversely affect competition. “The facilities market is highly concentrated, and there is a lack of competition or innovation amongst the largest facility groups. Competition in the funder market, to the extent that it exists, does not place the consumer at the forefront. The practitioner market is characterised by both unilateral and coordinated conduct which does not necessarily benefit the patient,” the committee was told.

An interesting point made by the HMI was a feature unique to the South African funders market in that medical schemes are not for profit, but their administrators are for profit. “This phenomenon was poorly understood by medical schemes.”

There has been inadequate stewardship of the private sector, the inquiry found. “Failures include the Department of Health not using existing legislated powers to provide oversight of the private healthcare market; failing to ensure regulator reviews, as required by law; and falling to hold regulators sufficiently accountable.”

As a result of these failings, noted the HMI in its report, “the private sector is neither efficient nor competitive.”

The parliamentary committee noted that the HMI report provides an evidence-based diagnosis of the private health sector and offers remedies. However, the report requires an in-depth study through a workshop to look at the recommendations in order to ensure implementation. It said it will process the report with the trade and industry portfolio committee.

Some of the HMI’s key recommendations include:

- The establishment of a new independent supply-side regulator for healthcare, which would, among other tasks, ensure effective and efficient regulatory oversight of suppliers of healthcare services, such as health facilities and practitioners. The HMI emphasised that this regulator must be “an independent and transparent public entity, in line with international practice where there is a clear shift towards regulatory independence in the healthcare sector”.

- Competition authorities must review their approach to creeping mergers in the facility sector;

- The introduction of a stand-alone, comprehensive standardised, obligatory base benefit package which “will increase transparency and allow consumers to readily compare options” while a simpler, less ambiguous design of the benefit package will help members to understand their cover;

- Remuneration packages of executives, principal officers and trustees should be linked more explicitly to the performance of schemes;

- The broker system to become an active opt-in system, with members being able to decide on an annual basis if they want to use a brokerage. For those who do not, the membership fees will be lower;

- A review of the ethical rules of the Health Professions Council of South Africa is required to promote innovation in models of care. The current rules, says the HMI, inhibit the innovation that needs to take place for creating value-based services;

- The introduction of outcomes measurement and reporting, as the absence of reliable information on health outcomes in the private healthcare sector is one of the key competition challenges.