|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

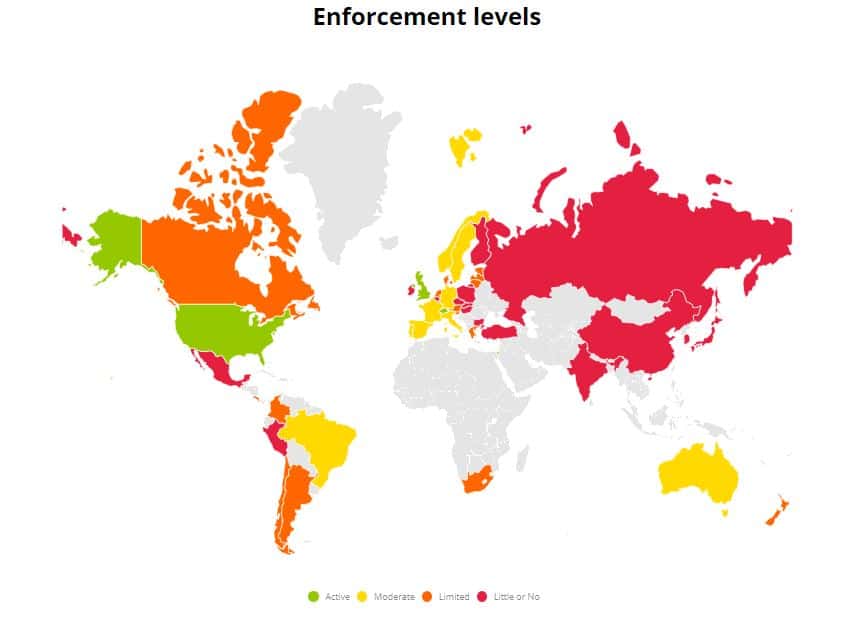

In 2018 Transparency International released a further edition of its Exporting Corruption survey, a progress report which rates countries based on their enforcement against foreign bribery under the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. The OECD convention requires signatory countries to criminalise bribery of foreign public officials and introduce related measures.

That report highlighted South Africa’s failure to make significant progress on convictions of foreign bribery; while 15 formal foreign bribery investigations were opened between 2014 and 2017, three cases were closed as at December 2017 and there were no convictions for foreign bribery.

The 2020 edition, released today, shows that nothing has changed. South Africa’s enforcement of the OECD convention was categorised as ‘limited’ then, and the country has not broken free of its limited status.

The 47 countries assessed – 43 of which are OECD signatories – are ranked in four categories: ‘Active’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Limited’, and ‘Little or No’ enforcement. Together they are responsible for some 83% of all global exports. In this context, foreign bribery is a serious threat to development as it creates significant economic repercussions, triggers unfair competitive advantages and results in fewer public services for the people who need them most, says TI.

But more than 20 years after the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention was adopted, nearly half of world exports – 46% – come from countries that fail to punish foreign bribery, with either limited or no enforcement.

SA failing to meet anti-corruption commitments

In terms of investigations, from 2016 to 2019 South Africa opened 14 investigations and commenced one case, while not concluding any cases with sanctions. As an example, the report notes that the investigation into MTN’s dealings in Iran and Turkey has been dragging on since 2012.

When it comes to the transparency of enforcement information, South Africa is not forthcoming with such information. Data on mutual legal assistance (MLA) is released only under freedom of information requests, and is not published as a rule.

Most concerning is the fact that there is still no central register of beneficial ownership information in South Africa. The TI report states that the country has undertaken a national risk assessment of beneficial ownership transparency of trusts and is considering moving toward creating a beneficial ownership register. Such a tool would possibly fall under the Treasury’s auspices.

The time for merely considering is long past, however. As a G20 member South Africa has long been committed to implementing the global bloc’s High-Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency, adopted in 2014 – but the G20 itself has failed to implement its own resolution at anything faster than a snail’s pace.

Furthermore, under its membership of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) South Africa has also committed to addressing the matter in its third national action plan, filed in 2016. At that time Corruption Watch was already calling for a public register of company ownership, which has not materialised.

In OGP matters, too, South Africa has fallen well short. Commitment 8 of the national action plan – a) implement the G20 High Level Principles, and b) implement a register of legal persons and arrangements – exists only on paper.

By 1 January 2020 – 4 months after the deadline of 31 August 2019 – South Africa had not drafted its fourth country action plan. The country was given until 31 August 2020 to submit the action plan. However, it has acted contrary to OGP process for two consecutive action plan cycles and has been placed under review, which could lead to an embarrassing expulsion from the OGP. As South Africa is one of the OGP’s 8 founding governments, this would be humiliating in the extreme.

Other findings

The TI report identified the lack of provision for deferred prosecution agreements as a major inadequacy in South Africa’s legal framework, as it hinders law enforcement authorities’ ability to detect foreign bribery, and severely limits the scope of voluntary disclosure by companies.

The OECD working group on bribery noted, in its Phase 3 follow-up report issued in 2014, noted that “sanctions for legal persons remain low, particularly where foreign bribery cases fall under the jurisdiction of the Regional Courts”.

TI pointed out another weakness, this one relating to inadequate resources in the enforcement system. This was a major issue until recently, says the report, as investigators and prosecutors were overburdened with cases. While the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has filled several vacancies in the past year, there is still cause for concern.

Recommendations

- Systematically publish enforcement data on foreign bribery, as well as on MLA requests made and received by South African authorities

- Create a publicly accessible register for beneficial ownership information

- Approve legislation providing for deferred prosecution agreements, as an important tool in foreign bribery enforcement

- Increase institutional capacity to detect, investigate and prosecute foreign bribery

- Increase available sanctions for legal persons convicted of foreign bribery

- Strengthen whistle-blower protection

- Dedicate adequate resources to anti-corruption enforcement agencies.

Silver lining in a grey cloud

The 2020 Exporting Corruption report does commend President Cyril Ramaphosa’s efforts to strengthen law enforcement agencies, and says: “The dramatic change in political climate since 2018 has had a positive impact on agencies’ capacity and willingness to investigate foreign bribery.”

It notes that additional funds of up to R2.4-billion have been set aside for the NPA, the Hawks and the Special Investigating Unit. This will cover the appointment of approximately 800 investigators and 277 prosecutors who will deal with among others, clearing the case backlogs – such as those of the Zondo commission into state capture – and foreign bribery investigations.

The report also mentions the formation of a multi-agency task team, which meets monthly to discuss the status of ongoing foreign bribery investigations and possible new investigations, and to identify challenges.

The task team comprises representation from the Hawks, the NPA, the Department of Public Service and Administration, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, the Treasury, the South African Revenue Service, the South African Police Service and Interpol, the Financial Intelligence Centre, and the Master of the High Court.