|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

South Africa’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are not what could be described as the pride of the nation. The likes of Eskom, the Passenger Rail Association of South Africa (Prasa), the South African Post Office (SAPO), South African Airways (SAA), the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), and others have become a national embarrassment rather than a national treasure.

At the heart of the SOE woes lies gross mismanagement and incompetence, irregular spending and poor governance. In fact, this situation has contributed in a large part to the national economic crisis. And the taxpayer ultimately foots the bill, to the tune of billions of rands.

In his 2016/2017 audit outcomes report, auditor-general Kimi Makwethu identified the main culprits. When it came to irregular expenditure, the top contributors were the Airports Company of South Africa, SAPO and the SABC, at R1.17-billion, R719-million and R687-million respectively. That’s around R2.5-billion that we cannot afford to lose.

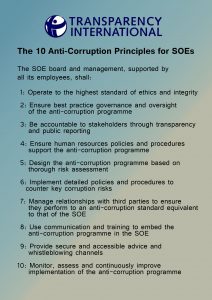

Recently global anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International (TI) published 10 Anti-Corruption Principles for State-Owned Enterprises, a guide to encourage and help enterprises controlled or partially owned by the state to implement best-practice anti-corruption programmes based on the highest standards of integrity and transparency.

SOEs, says TI, represent a significant proportion of many countries’ GDPs, especially in emerging markets, and are often a country’s largest employer. They are responsible for the provision of crucial services such as energy, water, transportation and healthcare to communities.

Compared to other companies, SOEs have specific corruption risks because of their closeness to governments and public officials and the scale of the assets and services they control. Some of the biggest recent corruption scandals have involved state-owned enterprises, which clearly shows the risks that these companies face.

In Brazil, the state oil company Petrobras was the focus of a major corruption scandal involving illegal payments to politicians and bribes that led to immense economic, political and social damage that affected the whole country. The Nordic telecoms giant Telia was recently caught bribing for business in Uzbekistan, which resulted in fines of US$965-million.

In South Africa many SOEs are in deep financial trouble, relying on bailouts and guarantees from government – all funded by taxpayers – to survive.

“The most effective way for SOEs to combat corruption is through transparency. This is at the heart of the SOE principles,” said TI’s new chairperson, Delia Ferreira Rubio. “Because SOEs are owned by the public, they should be beacons of integrity and transparency. Unfortunately, this does not always seem to be the case.”

The SOE principles provide a code for ethical behaviour and a practical framework to counter corruption risks. In particular, they emphasise the role of corporate governance in providing accountability to stakeholders through transparency and public reporting. If the principles are followed closely, they will help SOEs to run efficiently and be transparent and accountable to their ultimate owners – citizens.

The SOE principles were developed through a multi-stakeholder process where TI sought advice and recommendations from SOEs themselves, its chapters, academics and governance experts from around the world. They are aligned to TI’s 2003 Business Principles for Countering Bribery, which were updated in 2013 – these principles have contributed significantly to shaping corporate anti-bribery practice.

The SOE principles are also designed to complement the work of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development on providing corporate governance and anti-corruption guidance to governments.

The 10 principles for SOEs

The SOE board and management, supported by all its employees, shall:

The SOE board and management, supported by all its employees, shall:

- Operate to the highest standard of ethics and integrity;

- Ensure best practice governance and oversight of the anti-corruption programme;

- Be accountable to stakeholders through transparency and public reporting;

- Ensure human resources policies and procedures support the anti-corruption programme;

- Design the anti-corruption programme based on thorough risk assessment;

- Implement detailed policies and procedures to counter key corruption risks;

- Manage relationships with third parties to ensure they perform to an anti-corruption standard equivalent to that of the SOE;

- Use communication and training to embed the anti-corruption programme in the SOE;

- Provide secure and accessible advice and whistleblowing channels;

- Monitor, assess and continuously improve implementation of the anti-corruption programme.